Intercolonial conflict passed through several distinct stages. At first there was an impromptu quality to much of the conflict that was determined by the size of settlements. When Quebec City was small, it took little more than a couple of boats out of Boston to cause it grief or to capture it. In the 1600s these were settlements of a few dozen people, none of which were ferociously loyal to the towns they defended. Protecting Quebec in 1629 was more like protecting a warehouse than a community.

There is, as well, an entrepreneurial aspect to conflicts in the 17th century and among some of the wars and raids of the 18th century. Privately-funded attacks on enemy colonies were typical of raids out of New England. These were conducted by merchants, investors, and local government officials, not the British Navy. They had personal gain and the protection of their own interests at heart, rather than those of the Empire. Even George Washington’s disastrous invasion of the Ohio Valley on behalf of the Commonwealth of Virginia was not conducted as the business of Britain.

Threaded throughout these two centuries, too, were conflicting imperial agendas. Tensions in Europe regularly spilled over into North America: a continental war could easily become an intercolonial war. Historians of Canada have long pointed to this fact, highlighting the exception of the Seven Years’ War that began in North America before being taken up in Europe. That narrative, however, often overlooks the almost continuous wars between Aboriginal forces and their European neighbours. The background to some of these intercolonial conflicts is, in fact, decades-old struggles between colonial nodes and Aboriginal nations. One difference is that an official European war might produce additional military or naval resources for the colonists to use against their indigenous opponents.

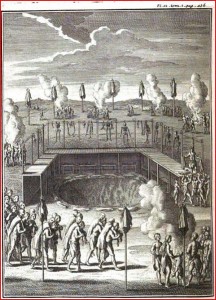

There is also the quality of warfare to consider, specifically the contrast between guerrilla warfare and the use of well-drilled European armies and colonial militia. The character of warfare changed through the 18th century, becoming increasingly European in style and focused much more on the role of professional soldiery and less on the use of terror and fire by both European and Aboriginal participants. The latter style persisted but the standing army was only a revolution away.

Behind all of this lay a growing economic presence in North America. New France had become a functional social and economic colony. By 1759 generations had been born and raised in the St. Lawrence with no firsthand knowledge of France. The same, of course, was true of the diverse settlers and slaves in the Thirteen Colonies. The economic presence, then, was both imperial and local. The creation of successful colonies always carried with it the possibility that local sensibilities would emerge. Some of these, of course, would conflict with those of empire.

Key Terms

Acadian Expulsion: The removal of Acadians and other francophones from Île Royale after 1745, and accelerating after 1755 as the British forcibly removed the larger portion of the colonist population. In French it is called Le Grand Dérangement.

Annapolis Royal: British name for Port Royal.

Battle of Sainte-Foy: Battle on April 28, 1760, near the citadel of Quebec with the French/Canadien forces attacking the British. General Murray repeated many of the errors of Montcalm only months before. The British survived (having suffered more than a thousand casualties) by hunkering in the fortress until British naval reinforcements arrived.

bourgeois, bourgeoisie: Originally someone who lived in the town (French: bourg; German: burg; English: borough), typically associated with merchants, professionals, etc. By the 18th century the bourgeoisie emerged as a distinct social class, a “middle class.”

Chemin du Roy: The “King’s Road,” built in the 1730s; a major infrastructure project in its time. One of the longest continuous roads in North America, it connected seigneuries on the north shore of the St. Lawrence.

coparcenary: A system of joint/shared inheritance of property.

East India Company: Established in 1600, the largest of Britain’s chartered trade monopolies. It dominated trade and was an instrument of British imperialism in Asia and was the model on which the Hudson’s Bay Company was based.

Father Le Loutre’s War: (1749-1755) Also called the Mi’kmaq (or Micmac) War, a conflict that pitted the Mi’kmaq and some of the Acadian communities against the British and New England interests in Nova Scotia. Name derived from the role played by Catholic Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre, a missionary who led the French, Acadian, and Wabanaki forces.

Father Rale’s War: (1722-1725) Named for Father Sébastien Rale, a Catholic priest who nominally led the Wabanaki forces, this conflict is known by several other names as well. It was provoked by New England expansion into unceded Wabanaki territory in what is now Maine and New Brunswick. The French were allied with the Wabanaki against the British and New England forces.

feudalism: An economic and landholding system of social, legal, and military customs based on notions of mutual responsibility. Land ownership was typically by a manorial elite for which a peasantry laboured. The aristocratic landowners, in turn, owed labour to the higher nobility, including the king.

Fortress Louisbourg: Established in 1713 as a fishing village, an important fortified centre of trade and naval activity from the 1720s on. Louisbourg was one of the largest towns in New France by the 1740s and an important asset in French efforts to harass the British in Acadia. Twice captured by the British and New Englanders, it was largely demolished in 1758.

free trade: A philosophy of commerce that calls for limited or no tariffs and protectionism. Free trade is in stark contrast to mercantilism.

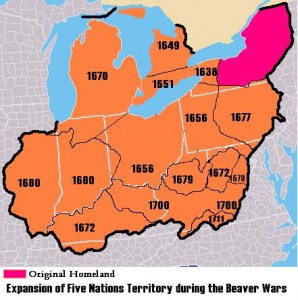

Great Peace of 1701: Also called the Great Peace of Montreal; a treaty struck between New France and 40 Aboriginal nations. The Great Peace drew to an end the long-running war between Canada and the Haudenosaunee Five Nations and what had become known in some circles as the Beaver Wars.

guard hairs: The barbed outer hairs found on many mammal pelts, typically longer than the underpelt and more easily shed.

guerrilla: A form of warfare distinguished by the lack of structure and organization typical of formal warfare. Characterized by ambushes, small units, and lightning raids, guerrilla warfare aims to demoralize and wear down a larger opponent that lacks the same speed and mobility.

Gulf Stream: A strong current that runs from the Caribbean along the east coast of North America, across the Atlantic, and along northwestern Europe. It accelerates sea traffic heading east and can impede vessels heading west.

illicit trade: In the context of mercantilism, unsanctioned trade between colonies.

indentured servants: Individuals contracted on a multi-year, fixed-term basis to work in the colonies. Usually taken up by young men and women whose passage would be paid by their employer. At the end of the indenture young men would typically receive a new suit. Large numbers of migrants from Britain to the Thirteen Colonies are thought to have started in indentured servitude. This system was regularly abused and, in some circumstances, was barely distinguishable from slavery.

Le Grand Dérangement: See Acadian Expulsion.

Loyalists: British-American colonists who were opposed to the revolutionary position struck by other colonists. At the end of the Revolution, many Loyalists joined an exodus to other parts of British America, particularly Nova Scotia and Quebec.

Mi’kmaq War: See Father Le Loutre’s War.

New Amsterdam: The Dutch colonial settlement at the mouth of the Hudson River in what was called New Netherland. Subsequently renamed New York.

New England: In the pre-Revolutionary years refers to the British colonies of Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Massachusetts, along with the territory roughly described now by the State of Maine.

nursery of the navy: The Grand Banks and other fisheries in the northwest Atlantic that were regarded by imperial powers in Europe as training grounds for sailors and recruitment grounds for their respective navies.

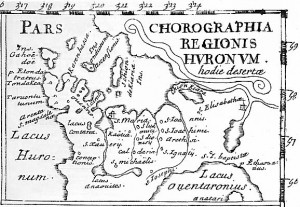

Pays d’en Haut: A part of New France containing much of what is now Ontario, the whole of the Great Lakes, and notionally all the lands draining into them. Extended as far as the Upper Mississippi and the Missouri. Translates roughly into the “upper country.”

Plains of Abraham: Located near to the Citadel of Quebec; the site of what proved to be a pivotal battle between British and French/Canadien/Aboriginal forces in September 1759.

planters: Some 2,000 settlers in Nova Scotia in the period between the Acadian Expulsion and the 1780s, drawn from New England.

primogeniture: System of inheritance that favours the eldest male offspring. Compare with coparcenary.

regicide: The murder of a king.

staple: A raw material or unprocessed product. Fish and furs were primary staples in the early colonial economies of New France and British America. Lumber and grain were later staple exports from New France and British North America. For the staple theory, see Chapter 9.

status quo ante bellum: A term used in treaty-making meaning a return to how things were before the war.

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748): Concluded the War of the Austrian Succession. Restored the status quo ante bellum in North America.

Treaty of Paris (1765): Ended the Seven Years’ War. France ceded all of its territory east of the Mississippi (including all of Canada, Acadia, and Île Royale) to Britain and granted Louisiana and lands west of the Mississippi to its ally Spain. Britain returned to France the sugar islands of Guadeloupe. France retained St. Pierre and Miquelon along with fishing rights on the Grand Banks.

Treaty of Ryswick (1697): Terminated the War of the League of Augsburg; restored the status quo ante bellum in North America.

Treaty of Utrecht (1713): Ended the War of the Spanish Succession. French claims on territory in Newfoundland and on Hudson Bay were ceded to Britain as was Acadia (Nova Scotia) except for Île Royale and Île Saint-Jean.

Short Answer Exercises

- In what ways did English expansion into North America in the 1600s contrast with New France?

- How did mercantilism shape colonial North America as a whole?

- What was the impact of the seigneurial system on the development of New France?

- Why did towns remain small in Newfoundland and in New France?

- How did the colonial world fit into the larger Atlantic Rim economy?

- In what ways did English expansion in North America in the 1600s and 1700s challenge the French presence in North America? How did France respond?

- To what extent were colonial conflicts a product of imperial rivalries, as opposed to local issues?

- To what extent were inter-colonial conflicts bound up in Aboriginal agendas?

- Detail New France’s liabilities and assets in confronting the English colonies from 1689 to 1760.

- In what ways was the experience of Acadians different from that of Canadiens?

- After initial French successes in the Seven Years’ War, why was Britain able to gain the upper hand in 1757?

- Why were the “neutral French” deported in 1755 and not at an earlier point between 1713 and 1755?

- Why did New France fall?

Suggested Readings

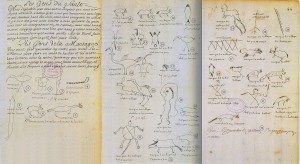

- Balvay, Arnaud. “Tattooing and its Role in French-Native American Relations in the Eighteenth Century.” French Colonial History 9 (2008): 1-14.

- Dewar, Helen. “Canada or Guadeloupe?: French and British Perceptions of Empire, 1760-1763.” Canadian Historical Review 91, no.4 (2010): 637-60.

- Griffiths, Naomi. “The Decision to Deport.” In From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755 , 431-64. Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005.

- Wicken, William. “Mi’kmaq Decisions: Antoine Tecouenemac, the Conquest, and the Treaty of Utrecht.” In The Conquest of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, and Aboriginal Constructions, 86-100. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Attributions

This chapter contains material taken from U.S. History created by OpenStax College. It is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license.

This chapter contains material taken from U.S. History created by Boundless. It is used under a CC-BY 4.0 International license.

This chapter contains material taken from the Wikipedia page, “History of Newfoundland and Labrador,” is used under the CC-BY-SA 3.0 unported license.