Carleton wasn’t the only governor facing recalcitrant and angry merchants. The cost of the Seven Years’ War in North America was significant and the British Treasury looked to the colonies to recoup some of the Crown’s expenses. Taxing the people who were supposedly the principal beneficiaries of the Conquest (that is, the British-Americans) seemed like a good and fair idea.

Revolutionary Colonies

The British Thirteen Colonies had been administered by what came to be known as “salutary neglect,” a kind of autonomy in everything but name. Each colony’s assembly was in some measure distinct and all had their own particular kind of relationship with Britain. One commonality, however, was the notion that the Colonies were not to be taxed. Resistance to taxation without representation had a long history in the Colonies and it flared up in the 1750s, the 1760s, and — finally — in the 1770s. As King George III’s government pushed in the direction of more direct and authoritarian rule over the colonies, the colonists themselves were pulling in a different direction. Philosophical discussions regarding classical views on democratic principles and rights became widespread and informed a Whig challenge to imperial rule. Thomas Paine (1737-1809), an English immigrant to America in 1774 who popularized new ideas associated with human rights, provided much of the vocabulary needed to mobilize colonial support for revolution. At the same time, there were scores of merchants and investors in the main port cities who saw glory and prosperity in a future outside of British trade constraints. The Revolution, then, was spurred by a desire to conserve existing rights, an aversion to taxes, awareness of opportunities for wealth-making, and a suite of truly revolutionary ideas about who should govern whom.

Some colonists rejected the revolutionary approach. Perhaps as many as one in five Americans advocated loyalism: finding ways to continue living under British rule. The Loyalists took positions across a broad spectrum and were motivated by very different concerns. Some were Tories who rejected the ideas of Paine and the prospect of change of any kind. They were at one end of the spectrum. Others took the perspective that negotiations with Britain could improve relationships without sacrificing two centuries of deep cultural, economic, and political connection. The Haudenosaunee, for their part, had a long-standing relationship with Britain, and the Seneca/Mingo and Mohawk in particular were anxious about American colonists’ hunger for their lands. Iroquois loyalists were to play a key role in the British military campaign. (Ironically, the Boston protesters of 1773 chose to disguise themselves as Mohawks when they attacked the tea ship, the Dartmouth.)

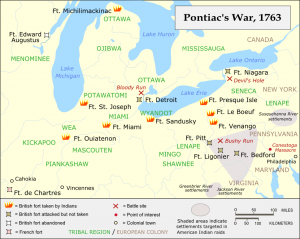

Settlers along the Ohio Valley frontier, especially German and Dutch immigrants, had survived Pontiac’s War and continued threats from Aboriginal neighbours only because of the protection offered by British soldiers and forts. They had little connection to the rising discontent in New England or Virginia and good cause to be favourably disposed to the British. African-American slaves were promised their freedom by both sides in the conflict and a great many elected to join the British against their owners. To the north and east, whole colonies rejected the Revolution.

Revolutionary Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland

The Patriots — the American revolutionary leadership — had good reason to expect support from the Canadiens. After all, more than any other colony they were living under British rule and an unelected, oligarchical administration. Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) famously claimed that winning Canada away from Britain was “a mere matter of marching.” France — always happy to put a stick in Britain’s spokes — discretely supported revolutionary feeling in the province. American agitators went from town to town cajoling and threatening Canadiens to thrust off Europe and accept a North American destiny. Keep in mind that the Anglo-Canadian merchants of Montreal were hungry for democratic institutions, so the rhetoric of the Patriots appealed to many of them. Against this backdrop, the British turned to their carefully groomed allies among the seigneurs and the clergy to encourage Canadien loyalism. Both sides were disappointed. The Canadiens failed to rise up against the British and they did little to push back the Americans’ invasion.

Generations of war between New England, New York, Acadia, and Canada had taught the Americans to watch the northern frontier. The British already had a strong military presence there; if it was speedily reinforced it would become a base of operations against the Revolution. The Patriots sent their new continental army north in the spring of 1775, early in the conflict, hoping to fire up the Canadiens and dislodge the British. They failed on the first count but were able to drive Carleton’s forces from Montreal and push him back into the citadel at Quebec City.

The Canadiens were not fans of the British regime but they hated — or at least deeply mistrusted — the New Englanders at least as much. Like the Acadians before them, the Canadiens pursued a self-interested neutrality, supplying both sides (sometimes at an inflated profit) and generally staying out of the way. Although Bishop Briand was disappointed by the lacklustre response of the populace to his call to arms, the clergy may have been successful in fanning the flames of anti-Protestant sentiment. Certainly the Church believed it had much to fear in the rhetoric of the Patriots. Hierarchical elements of life in Quebec, then, were factors that both dampened and incited revolutionary sympathies among the Canadiens.

Carleton, for his part, was able to repel the two-pronged American attacks on Montreal and Quebec but he was unable — even with British reinforcements — to press the advantage home. By 1777 the Patriots had given up hope of a northern front against the British, and the British had reoriented their efforts to the tidewater ports.

The situation in Nova Scotia was more complex. There, the post-Expulsion population was made up of English and Scots settlers at Halifax along with a garrison of soldiers and hangers-on, New Englanders — or Planters — who had come northeast to take up farmland, an infusion of more than a thousand farmers from Yorkshire who emigrated because of worsening economic and tenancy conditions at home, and German and other non-anglophone immigrants (some of whom were relocated Pennsylvania Dutch). Efforts by the Nova Scotian regime to build the population had, then, met with some success. But the towns and settlements were ethnically distinct: the Chignecto Isthmus was dominated by New Englanders who were at odds with neighbouring Yorkshire immigrants. Lunenburg was the site of German/Swiss settlement and the target of repeated Mi’kmaq and Acadian raids. The 8,000 or so Planters focused on the Bay of Fundy, and the Pennsylvania Dutch worked their way up the Petitcodiac River to “the Bend” (a.k.a. Moncton). In the northeast of the colony, on the frontier of the Gaspé, returning Acadians were permitted to establish new communities. There was widespread instability throughout the colony in the 1760s as the Mi’kmaq War continued. By the time of the Revolution, Nova Scotia was still little more than a collection of loosely connected outports and farming villages with not much in the way of a shared identity.

New Englanders in the colony were, of course, interested in how events in Massachusetts appeared to be unfolding and there was some sympathy for a local insurrection against the British. The colonial governor was never in a particularly powerful position, despite the presence of the Royal Navy. Unlike the Province of Quebec, Nova Scotia had an elected assembly. But the electorate was a small one, made up of property owners and the pool of potential assembly members was, in practice, restricted to those men wealthy enough to participate. This left the merchant class of Halifax in a position of powerful influence. Corruption in their dealings with the military and administrative establishment was widespread; attempts to expose it ultimately cost Governor Francis Legge his job. Before that occurred, however, Legge was assigned the task of raising a colony-wide levy and a militia in support of Britain’s campaign against the revolutionary colonies to the west and south. This initiative was akin to prodding a hornet’s nest: the New Englanders — who constituted at least 50% of the Nova Scotian population — objected to the idea of fighting their kin and called for an end to the tax and the militia campaign. Realizing that he was on the brink of inspiring rather than suppressing revolutionaries, the governor prudently backed down.

This was not enough for some New Englanders in the colony. Two incidents occurred that deserve mention: the raids launched by freebooters out of the Machias Basin, and the insurrectionary efforts of John Allan (1747-1805) and Jonathan Eddy (1726-1804) in the Chignecto Isthmus. The former were using the Revolution as an excuse to line their own pockets, and they were badly disorganized and undersupported by their own people (that is, settlers from New England). The Allan and Eddy rising was divisive even among the New Englanders, who would have preferred waiting for a liberating army from the Thirteen Colonies.

George Washington (by this time a general in the Continental Army) refused requests to intervene, citing the presence of the Royal Navy at Halifax and the strategic challenges of holding onto a prize that was in no way unified. The Yorkshiremen remained loyal to the British cause, what few Acadians and Mi’kmaq could be drawn into the conflict favoured the Patriots, but the pivotal population of New Englanders chose to remain neutral. Eddy’s attack on Fort Cumberland in November 1776 failed and Nova Scotia’s flirtation with revolution came to an end. Raids on outports by privateers working out of New England and New York thereafter only served to alienate the Nova Scotians further from the American cause.

Figure 7.5 Jonathan Eddy, leader of the failed rising for independence in Nova Scotia.

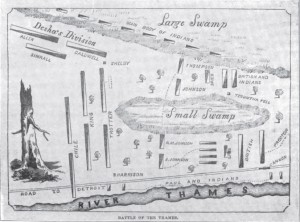

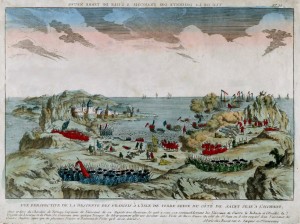

There are echoes of the Nova Scotian experience in Newfoundland. Both colonies had a British naval presence and a population that was disaffected from Britain (in the case of Newfoundland, large numbers of Catholic Irish immigrants). In Newfoundland these were not characteristics that either restrained or propelled support for the Revolution. The naval presence, for example, was an indifferent factor because it was so small and badly maintained. Newfoundland was a place where the navy harvested sailors, not one where it patrolled the waters. If there had been local discontent, it would have been difficult to muster and almost impossible to focus: the settlements were even smaller and more isolated from one another than on the mainland and there was barely any administrative presence at which to aim revolutionary fervour. In Newfoundland, the orientation of communities was toward the sea, the fisheries, and the export market, not toward one another. The population had little to do with New England and was in no way caught up in the rhetoric of the Revolution. What’s more, there was money to be made in loyalism: the Americans had been frozen out of the Grand Banks early in the war and the French left it as soon as it looked likely they’d join in on the side of the Americans. This left Newfoundland’s fishing fleet in a very good position to expand exports into both the West Indies and Europe. And, as was the case in Nova Scotia, the arrival of American pirates was unlikely to spark sympathy for the cause of the Thirteen Colonies. Finally, the French briefly captured St. John’s in 1762, which resulted in a British counter-invasion, all of which reinforced Newfoundland’s loyalty to the Crown.

Figure 7.6 The French capture of St. John’s, 1762.

The Loyalist Exodus

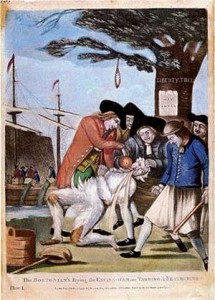

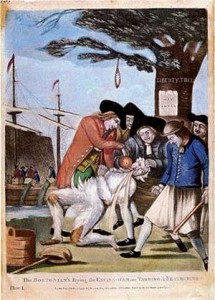

By July 4, 1776, the Patriots controlled the majority of territory within the Thirteen Colonies and expelled all royal officials. Colonists who openly proclaimed their loyalty to the Crown were driven from their communities, often violently. Bostonian Patriots set the tone in 1774 with an attack on a local customs officer, John Malcolm, and the practice of terrorizing officials and critics of the Revolution spread rapidly. Mobs, often calling themselves “Sons of Liberty,” harassed and brutalized suspected Loyalists or Tories using torture techniques such as tarring-and-feathering, locking them in stockades, and forcing “riding the rail” (that is, being straddled over and tied to a long wooden rail which was carried and bounced along in order to inflict injury to their genitals and thighs). All of these treatments were accompanied by public humiliation. Loyalist regiments were assembled across the colonies in support of the British cause and what is usually described as a battle between colonists and the Crown was, in fact, a civil war between American colonists. Mortality rates among the Loyalist regiments increased and levels of brutality on both sides were high.

After the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, Patriots equated loyalism with treason and meted out punishment accordingly. This is not to say that the British and their allies did not engage in brutal treatment of the Patriots; it is merely to point out the context of the Loyalist emigration.

Figure 7.7 “The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering,” attributed to Philip Dawe, 1774. John Malcolm, a tax collector is shown. He was subsequently hoisted into the liberty tree.

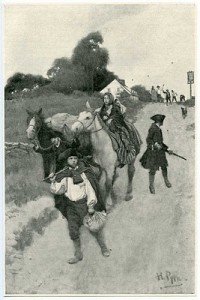

When the Loyalist cause was defeated, many Loyalists fled to Britain, Canada, and other parts of the British Empire. The departure of royal officials, rich merchants, and landed gentry destroyed the hierarchical networks that thrived in the colonies. Key members of the elite families that owned and controlled much of the commerce and industry in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston left the United States, undermining the cohesion of the old upper class and disrupting the social structure of the colonies. The largest number of these exiles made their way to Quebec and Nova Scotia, although the wealthiest and those who formerly held key positions in the British administration of the colonies were more likely to head to Britain.

Figure 7.8 “Tory Refugees on the Way to Canada” by Howard Pyle, 1901. This 20th century imagining of the Loyalist migration emphasizes the forced aspects of the migration.

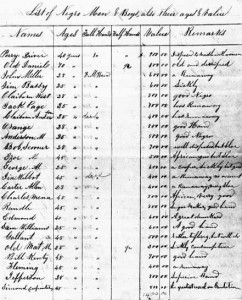

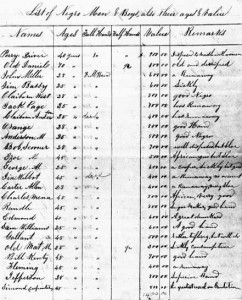

The Loyalist exodus to what remained of British North America consisted of a wide array of people. In a 1999 article in the journal Acadiensis, Barry Cahill makes an important distinction between Loyalists of colour (of which there were fewer than a hundred by his reckoning) and “fugitive” African-Americans who were “seeking refuge from slavery.” This second, much larger body of migrants were opposed to being chattel property, not to revolutionary ideals.[footnote]Barry Cahill, “The Black Loyalist Myth in Nova Scotia,” Acadiensis XXIX, no.1 (Autumn 1999).[/footnote] Some 3,000 African-American slaves — thanks in no small measure to Guy Carleton’s willful disregard for orders to obstruct their passage — travelled from New York to Nova Scotia. Most settled in and around Halifax, some taking up farming.

The refugee slaves were quickly caught in a legal grey area wherein they were regarded as “slaves” even though they might not have “owners.” The British regime took no steps to emancipate the Loyalists of colour, and some of the White Loyalists who had been slave owners before the Revolution expressed a desire to restore that system of relationships. In 1787 the British government arranged for members of the Afro-Nova Scotian community to relocate to the West African community of Sierra Leone, an offer that was taken up by many who were tired of bitter winters and shoddy treatment by White Haligonians. As the Nova Scotian historian Barry Cahill points out, the story of the Black Loyalists has become part of the narrative of inclusivity in Canada, but it is mostly a fiction: “One cannot right the wrongs of history by turning Black people into honorary Whites, fugitive slaves into Loyalists. To do so is to permit the colonization of Black history by White historical myths.”[footnote]Ibid.[/footnote]

Figure 7.9 A page from the Book of Negros, a tabulation of African-Americans heading from New York to Nova Scotia. Note that ages are mostly rounded and that “values” are provided.

Another group of “Loyalists” whose agenda was, like the African-Americans, distinct from those of the colonial Tories was the Aboriginal group of refugees. Roughly 2,000 Haudenosaunee, principally Mohawk, left their homeland for a large swath of what is now southern Ontario under the leadership of Thayendenaga (a.k.a. Joseph Brant, 1743-1807). Thayendenaga’s links with the British were diplomatic, military, and familial: he was connected to the British administration under William Johnson through his older sister, Konwatsi’tsiaienni (a.k.a. Degonwadonti, Mary Brant) who was Johnson’s consort.

The Haudenosaunees’ experience represents a further wrinkle or branch of what is too often presented as an unproblematic Loyalist mythology. Unlike the individual farming frontier loyalists of German and other European extraction who arrived nearby from western Pennsylvania and New York, the Mohawk Loyalists arrived and functioned as a group, as their own society. They injected into early southern Ontario a large and well-organized people well ahead of the settler waves that would travel up the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario.

The largest wave of Loyalist refugees — some 30,000 — headed to Nova Scotia. Like their pre-Loyalist Planter predecessors and Yorkshire-born neighbours, they took up land that had been cleared or drained by Acadians and began the arduous process of clearing hardwood forests for their new settlements. Many settled in areas where they might be depended upon to fight against invading American forces. The Saint John Valley in particular witnessed substantial Loyalist establishments, the most important being Fredericton. This new concentration of population led to the creation of a new colony, New Brunswick, whose political offices were immediately filled by Loyalists. Similarly, the colony of Cape Breton was briefly called into existence to administer the Loyalist arrivals there.

Roughly 10,000 Loyalists entered the Province of Quebec. There they encountered the seigneurial system of landholding, which frustrated attempts to settle the newcomers. Some went to the Gaspé and others into the Eastern Townships southwest of Montreal. The largest group that reached the St. Lawrence — some 7,000 — were sent upstream to the north shore of Lake Ontario.[footnote]Christopher Moore, The Loyalists: Revolution Exile Settlement (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1994).[/footnote]

Bisecting a Continent

The Treaty of Paris in 1783 reduced British North America significantly. The Province of Quebec lost Detroit and all the lands south of Lake Ontario and east of Lake Huron. There remained uncertainty about the boundary between Maine and New Brunswick; it would be unresolved for 50 years more. British forts in what the Americans now called their northwest were a sore spot for another decade as well until Jay’s Treaty impelled the British to leave the region for good. The Loyalist exodus helped decide other territorial claims as the British were then able to convincingly settle regions that had been in dispute.

It would be many years before British North Americans would begin to conceptualize their lands as something like “Canada,” but the outcome of the American Revolution nevertheless produced two separate entities. In some respects, it restored the old territorial division between England and France in North America before the Treaty of Utrecht (1713), although now Britain was playing the role in the north formerly played by France.

Key Points

- The American Revolution divided colonists in all the British possessions in North America along ideological, ethnic, and sectarian lines.

- Three British colonies — Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland — did not join in the Revolution, although factions within each supported it.

- Loyalists or Tories emerged in the Thirteen Colonies who eventually abandoned the United States at the end of the Revolution and formed a core population in British North America.

- A large proportion of the Loyalist migration comprised former African-American slaves and members of the Mohawk nation.

- The end of the Revolution established two separate colonial identities in North America, north of New Spain: the republican United States and the British-controlled and nominally loyal colonies collectively known as British North America.

Attributions

Figure 7.5

Colonel Jonathan Eddy by Hantsheroes is in the public domain.

Figure 7.6

Perspective view of the French attack on Newfoundland near St. John’s by Pierre5018 is in the public domain.

Figure 7.7

The Bostonians Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring and Feathering (1774) – 02 by Quadell is in the public domain.

Figure 7.8

Tory Refugees by Djmaschek is in the public domain.

Figure 7.9

2book0706b by Dr Wilson is in the public domain.