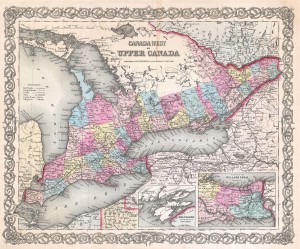

Figure 9.4 An 1855 map of Canada West (formerly Upper Canada) by Joseph Hutchins Colton. The counties are easily visible as are the growing number of towns and villages.

Upper Canada was the principal beneficiary of British emigration in these years — the destination of choice.[footnote]Hugh J.M. Johnston, British Emigration Policy 1815-1830: “Shovelling Out the Paupers” (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1972), 51–4.[/footnote] One consequence was that the sale of lands (and the speculation in land values) was a major source of wealth. Immigrants with a bit of money could buy ready-cleared properties or better located farms facing water routes that positioned them to realize success either in farming or in land resale. Against this setting, the market for British North American grain had taken a tumble after the end of the war, especially in 1820, and prices fell badly. Up to about 1816 the rapid growth in the British population discussed earlier needed feeding and had been the source of wealth for anyone who could produce a surplus of wheat. After two generations of slow pioneering farm expansion, Upper Canadians were finally in a position to do well on that market. The post-war economic crisis, coupled with increased production of wheat in the colony (much of it coming from post-war immigrants) made for increased competition in a shrinking market and, therefore, economic uncertainty.

Colonial Grain in Imperial Markets

Things were made more complex by the Corn Laws, which were protective tariffs put in place as part of the mercantilist system that channelled colonial products to imperial ports and limited colonial imports from non-imperial sources. The Corn Laws were introduced in 1815 and, for five years, British North American grain enjoyed the same privileged status on the British market as homegrown grain. Then, in 1820, British grain output improved and Upper Canadian wheat growers found their product reduced to the same status as “foreign” grain. For the next seven years farmers in British North America struggled along until their privileged status was restored. A wheat boom followed that lasted into the 1850s.

These developments further encouraged people to move into farming. The number of larger farms increased, and the number of acres under plough nearly doubled from 1826 to 1832. Farmers, too, stretched their productive capacity to take advantage of their place in the British market, which could mean going into debt.

Related to the growing farm economy was the rise of a colonial merchant class in Upper Canada that specialized in the wheat business. Their profits were tied to bulk shipping, so these merchants were inclined to support infrastructure improvements that benefitted the movement of bulk freight. Mostly this meant storage facilities, docks, shipping capacity, and eventually canals. Farmers, however, were more likely to want improvements in local roads. Some of the merchants discovered, too, that there was money to be made in transshipping American wheat and flour. Once the foreign product was in British North America it was treated as though it were covered favourably by the Corn Laws. When it came to raising revenues for government, business merchants (through the dominant political oligarchy) invariably supported property taxes and taxes on land sales while farmers (who were most hard hit by taxes) preferred duties charged on trade (which was anathema to merchants). These developments resulted in tensions between farmers in Upper Canada and merchants.

The staple theory, already discussed in terms of how it applied to resources like fish and furs, can be used to understand the wheat economy as well. The lack of diversification in the Upper Canadian farming economy is a symptom of the limits of a staple-dominated system. Tobacco was a popular crop in the 1820s, as was dairy production, but neither came close to wheat as a principal product. Wheat, unlike fur, is not a luxury product: a lot of wheat is needed to turn a profit. It is what economists refer to as a high-bulk, low-value product. It requires larger ships to move a greater volume, and that investment in specialized shipping does not necessarily support the movement of any other goods. In other words, grain ships are grain ships, not container ships that can carry a multitude of different products. Nor are they smaller, faster vessels designed to transport textile products. Further, any shipping requires the infrastructure of waterfront docks, warehouses dedicated to stockpiling grain, and improvements in shipping routes. Since the vast majority of British North American grain originated in Upper Canada, the priority was building canals in order to load up barges on Lake Ontario or even Lake Erie and send them downriver to Montreal or, better still, put the grain onto ships that could head straight out into the Atlantic.

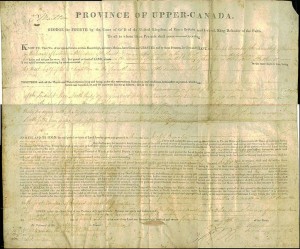

Figure 9.5 An 1824 land deed from Upper Canada. The buying and selling of farmland was a critical part of the colony’s economy and an important function of the government.

The Upper Canadian wheat economy comprised, therefore, several elements: profitable and speculative land sales; the business of land clearing (forestry) and preparing for farming (or sale); farming itself; and shipping. Given the privileged character of land grants in Upper Canada and the obvious fact that shipping is not something in which farmers are typically involved, most of the money in the wheat economy was made by people who did not actually work the land. Farmers did well and some did very well, but not so well as those who owned the infrastructure and the merchant houses responsible for the movement and sale of wheat.

It has to be added, too, that not all farmers were beneficiaries of the wheat economy. It has been observed that the self-sufficient farm in pre-Confederation British North America is something of a myth: farmers everywhere turned from time to time to other sources of income or revenue. In Upper Canada it was the larger and better capitalized farms that could afford to specialize in grain sufficiently to profit by the wheat economy. Rather than “mining wheat,” as it has been called, Upper Canadian farmers more often grew a variety of crops destined for the growing townships nearby with their expanding non-farming populations.[footnote]Marvin McInnis, “Marketable Surpluses in Ontario Farming, 1860,” in Perspectives on Canadian Economic History, ed. Douglas McCalla (Toronto: Copp Clark Pitman, 1987), 55.[/footnote] Obviously, for the multitude of smaller farming households, the construction of canals was of little value: they needed roads to transport their wheat to town markets.

Key Points

- The Upper Canadian economy was based on a combination of wheat farming and land sales, which had a reciprocal relationship.

- The wheat economy was highly vulnerable to changes in the trade environment with Britain, and this was beyond the control of the colonials.

- Buying and selling land, along with marketing wheat in the Atlantic, generated a merchant and financial elite in the colony.

- The character of the wheat economy determined where resources would be spent to build up infrastructure.

Attributions

Figure 9.4

Canada West by BotMultichillT is in the public domain.

Figure 9.5

Province of Upper-Canada land deed by BrianJGraham is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.