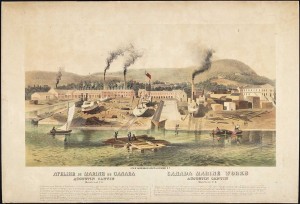

Figure 10.4 Water-powered grist mills like this one near Waterloo, Ontario, were common features in the countryside.

Life on the land in the 19th century was not insulated entirely from changes occurring elsewhere. In fact, the countryside was often where change originated. It was also where intensely conservative impulses could be found.

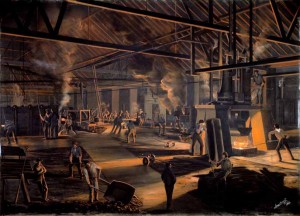

In a study of seigneury communities near Trois-Rivières, historian Colin Coates reveals the connections between landscape, community, social relations, and economic transformation. At Batiscan attempts were made at the beginning of the century to establish an ironworks, something which would have provided seasonal, part-time, and full-time/year-round work for locals. This was an attractive proposition in part because the habitants’ farmlands had been so severely divided across generations that their productivity was quickly diminishing. These conditions were a product of rising human fertility and family size in the Lower Canadian countryside; in a Malthusian sense the growth that food production had made possible could not now keep pace with the population it produced.

Young men found it more and more difficult to establish the kind of economic security that would allow them to marry, which forced some to leave the land for opportunities in the woods or in the towns, ideally to find land grants elsewhere, perhaps nearby, but these options were increasingly unlikely. Some of the seigneuries thus became densely packed rural enclaves in which community members were heavily dependent on one another while also quite competitive. The Batiscan ironworks held out the hope of wealth from something other than the finite resource represented by land. The failure of the ironworks project wasn’t a disaster, but it set back the hopes of the seigneury for a while.

All this happened in less than a single generation, and the result was country life returning to its agricultural focus.The countryside continued to generate food but it was increasingly focused on subsistence. In a sense, it became even more intensively agricultural than it had been during the days of the fur trade. An outsider visiting for the first time in the 1830s might mistake it for a very traditional agrarian landscape. In truth, the “tradition” only went a generation or so deep. In 1790 there were fewer than a thousand people in Saint-Anne and 1,281 in Batiscan; in 1825 the numbers were 2,175 and 2,454 respectively. The two communities were doubling in size at a roughly Malthusian rate. They were, as well, shedding large numbers: nearly 500 people left Batiscan between 1790 and 1825 — a fifth of the total population in 1825. What is more, household sizes were rising. At Batiscan in 1784 the average family size was about five; in 1825 it was around six.

Coates identifies one of the consequences of these changes: “As households grew larger and young men and women remained dependent on their parents for longer periods, hierarchical relations within the family were strengthened.”[footnote]Colin M. Coates, The Metamorphosis of Landscape and Community in Early Quebec (Montréal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000), 58-60.[/footnote] This hints at the changes in the status of elders and the roles of mothers and fathers. Rather than being viewed as a place in a state of stasis, these seigneuries (and they are probably exemplary of many more) were undergoing profound changes.

Class in the Countryside

Class relations were also under pressure. As Cole Harris observes, land shortages played into the hands of seigneurs. Too many people and too little land meant that labour costs fell, making it more feasible for seigneurs to hire workers to improve their own lands. Between 1791 and the 1830s, seigneurs were more likely to insist on payments of debts, which they lacked the leverage to do in previous decades. They even increased the cens et rentes, something they were unable to do under the ancien régime’s regulating hand. One effect was the rise of a seigneurial class that was more aristocratic (at least in its wealth and its manorial lifestyle) in the 19th century than it had been in the days of New France.

Harris notes that Lower Canada was, perhaps perversely, becoming more rural than urban in the 19th century. At the end of the French regime, one-fifth to one-quarter of the population of the St. Lawrence Valley lived in the towns, a figure that dropped to one-twentieth “of the French-Canadians” by 1815. This change took place in an era where the population as a whole jumped from 70,000 to more than 300,000. The main cities were becoming more English and less welcoming to francophones, but that doesn’t mean that the Canadien population retreated into the countryside. In order for those numbers to work, they only had to stay put on the land, have more babies, and stay out of the cities, which is exactly what happened. Small wonder that Canadiens saw the institutions of the countryside (the parish church and the parish priest, the seigneur and the manor house, the Coutume de Paris with its focus on family rather than individual) as fundamental to their way of life, even if each of those was at one time or another exploitative of their rural existence.[footnote]Cole Harris, “Of Poverty and Helplessness in Petite-Nation,” Canadian Historical Review 52, issue 1 (March 1971): 23-50.[/footnote]

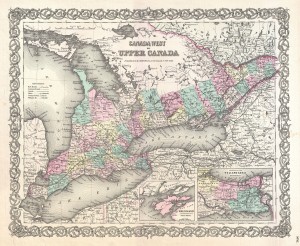

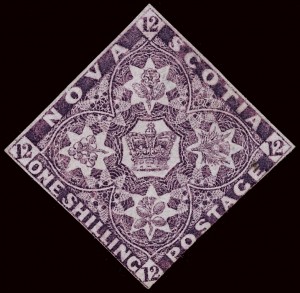

The situation in the English-speaking world was quite different. While the economic model of the family farm was found throughout all of British North America, it meant something different in the patrilineal nuclear family households of the anglophones. The availability of land in the western stretches of Upper Canada ensured that competition for inheritances would not produce painfully small subdivisions of farms. Communities stood in for families when it came time to depend on group labour for harvests, threshing, road building, and barn raising. The same was not always true in the Atlantic colonies, where poorer soil conditions and limited availability of arable land created pressures on locals to find other sources of income. In Prince Edward Island farming was an easier proposition, but often Maritime farming families looked to sawmills and mines to provide part-time and seasonal work. The family farm and the small market towns persisted, but they were rapidly becoming less typical of Maritime social organization.

Some of the changes occurring at the urban level diffused to rural areas, so much so that the clear cultural boundaries between town and country began to blur. Large edifices appeared, many of them made of brick and stone, to house new industries and institutions. In the early 19th century industry went to where there was water power: hydraulics were key to driving early factories. Once again, the river courses — especially the most difficult portage sites because that’s where the water power was to be found — were determining the shape of Canadian life.

Key Points

- Social relations in rural British North America were directly impacted by the availability of land and competition for space.

- Land shortages in Lower Canada reinforced and enhanced the authority and wealth of seigneurs.

- The countryside was not impervious to industrial life.

Attributions

Figure 10.4

Erb’s Grist Mill at Sunset by Russ Gordon is used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 license.