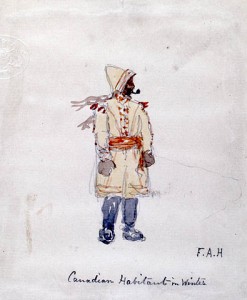

In 1815 the agricultural economy in British North America was just beginning to take off. The colonies had had a good war, on the whole. The Napoleonic years had, too, confirmed the primacy of the Tory oligarchies in each colony. While some of the old guard had been born into or fallen into their privileged positions, some — particularly the merchants and traders involved with the NWC and the HBC — had got there by hard graft and dangerous labour. Their sense of entitlement and the rightness of their leadership was palpable. And they felt threatened: the tide of history was against them (as seen in one revolution after the next), America was clearly a menace, and in Lower Canada there was always the French majority to fear. The Anglo elite sought to create social orders that would ease their concerns and enable their expansion.

By 1860 the Georgian Tory towns had been replaced (and in one important case, renamed). The urbanization of North America was still only in its early years but the rise of the city and town was underway. Middle-class men and women were beginning to impose their values and visions on the country from their seats in the media-rich port towns along the Great Lakes, the St. Lawrence, around the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and in Victoria, and New Westminster.

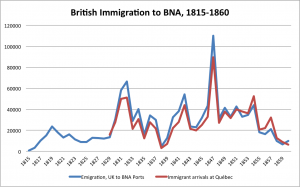

Even as this class of Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists was finding its voice, another population was pushing its way forward. The demographics of British North America were as dynamic in the second quarter of the century as they would be in the years between 1891 and 1914. The population was more diverse and sometimes conflicted. Issues of who belonged and how to treat those who did not arose in different venues and with varying degrees of force. Irish and Chinese alike would feel the limits of British North American generosity and welcome. Working people were another new variable: never before had there been so many people fully or at least heavily dependent on wages. Aboriginal people, too, found themselves exposed to the controlling impulses of middle-class and elite British North Americans who faced the future with both excitement and dread.

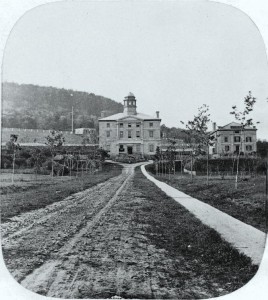

At the same time, the emerging middle classes sought conformity among their social inferiors and even the local aristocracy. The cities they were building and everything from their institutions (jails, schools, asylums) to the layout and naming of the streets reflected a growing middle-class consensus in British North America as to what citizenship looked like. The old bonds of deference to the gentry were giving way to a different order. The evolution of this tension from 1818 to 1860 is the subject of the next chapter.

Key Terms

anti-clerical: Associated with the secularist movement of the 18th and 19th centuries, anti-clericals took the position that the role of the church was the saving of souls and not schools and other institutions and certainly not politics.

benevolent societies: Also called “friendly societies” or “mutual societies,” a kind of cooperative organization in which the members pay subscriptions as insurance against illness, injury, widowhood, etc. Benevolent societies still exist but many have been supplanted by insurance companies and state welfare systems.

Chinatown: Urban areas dedicated to the housing and businesses of Chinese immigrants and their families. Some Chinatowns appeared spontaneously and were built by the Chinese community; others were imposed by the dominant Euro-Canadian regime as a means of containing the Chinese population.

civic buildings: In the 19th century, usually refers to city halls, local jails, and courthouses. Art galleries and museums as public facilities appear later. The erection of impressive civic buildings was a statement of civic pride, a means of promoting the community, and a statement regarding the growing power of municipalities.

civil service: Employees of the state/colonies/municipalities. Includes surveyors, land officers, postmasters, and a few other positions in the 19th century. The number and types of civil servants expanded with the size of the state in mid-century.

class consciousness: Awareness of one’s socioeconomic status (or “class”) and how it (a) creates and limits opportunities, and (b) is experienced by others as well and constitutes a set of common interests.

company store, company towns: Many 19th and 20th century resource-extraction and construction industries were situated outside of established communities; under those circumstances a great many provided housing, supplies, groceries, work clothes, fuel, churches, and any number of other services so as to attract, retain, and (when necessary) discipline their workforce.

cottage industry: A manufacturing process in which all or component parts of a product are assembled in a worker’s home. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries this was particularly associated with textile and clothing production.

crude birth rate (CBR): The number of births per 1,000 population.

crude death rate (CDR): The number of deaths per 1,000 population.

dependent population: The share of population under the age of 15 years and over the age of 60 or 65. The notion of “elderly” dependant varies over time depending on life expectancies and population health generally.

division of labour: In a system of production, the isolation of certain tasks that are assigned to individuals working cooperatively to generate a certain product. In shoe production, for example, one person may be responsible for the uppers and someone else for the soles and a third for stitching them together.

Famine Irish: Emigrants from Ireland who fled the Great Famine of 1845-52.

Foresters: The Ancient Order of Foresters (AOF), a benevolent society founded in England with branches globally and a focus on members’ insurance.

freemasonry: A fraternal organization dating from the 14th century, which serves principally as a network system between communities. It is a secret society with rituals derived from the medieval guild system. Freemasonry experienced rising popularity in English America from the 18th century and has always been regarded with suspicion and hostility by the Catholic Church and some other denominations, but not by the English Church.

gentlemen’s clubs: Organizations and facilities designed to support networking between business and society leaders. These were usually housed in elegant buildings near the centre of the business district. Until the late 20th century virtually none admitted women and most had sanctions against members of ethnic and religious minorities.

Grosse Isle: A small island in the mid-St. Lawrence River, about 50 kilometres downstream of Quebec City. Synonymous with quarantine of immigrants and epidemic mortalities.

guilds: Medieval institutions mostly organized at the local level around crafts, professions, and commerce. Merchants’ guilds often functioned as the civic authority while artisans’ guilds were a kind of trade union that defined the requisite skill levels for each craft and established controls on who and how many might be allowed to practise the craft. Increasingly criticized in the late 18th and early 19th centuries as being at odds with free trade.

hegemony: Control by one empire, class, faction, or religion over all others.

high culture, high style: Terms referring to the development of elite cultural activities, fashions, tastes, and practices in contrast with “folk,” “vernacular,” or “popular” culture. Examples include opera and classical music, baroque architectural styles, formal clothing, and elaborate culinary practices. High culture and style are typically enjoyed by a select number of people across a large — even global — expanse and the styles tend to change frequently; low culture or “vernacular,” by contrast is long-lasting and experienced by large numbers of people but typically in a small area. The cultural practices of Highland Scots, defined by durability and plainness of cooking and art, provide an example of a folk culture with limited external appeal.

higher education: College or university education. In the 20th century some vocational and trades training is included as well.

homespun: Originally referred to wools or other fabrics produced in the home but extends to full textile products also produced in the home. Synonymous with plain and simple, the term went from being a signal of artisanal skill to a derisory adjective meaning unsophisticated and unlovely.

House of Industry: First established under the British Poor Law as a refuge for the impoverished and/or bankrupt. The ideal of hard work even while receiving charity is reflected in the name. These were, as well, referred to as “workhouses.”

household wage: The combined income of all individuals residing as a household. Typically does not include unrelated boarders but does include servants.

ideals of womanhood: The dominant values in any given society pertaining to the most acceptable ways in which women should behave, the sort of character they should develop, etc. What falls outside of the ideal was often defined as deviant.

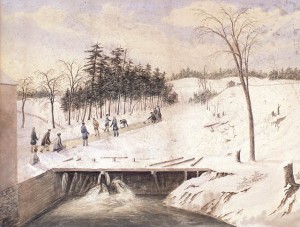

leisure time: Time left over after work obligations are completed. In 18th and 19th century agricultural societies, leisure time was associated with seasonal lulls between harvest and seeding, and sometimes between seeding and harvest. In early urban societies working people were assumed to have little leisure time outside of Sundays, which was officially or ideally given over as a day for prayer and reflection.

liberal professionals: Typically lawyers, physicians, notaries, accountants, journalists, printers and publishers, surveyors, and engineers. A cadre of urban skilled workers who were neither wage labourers nor members of the merchant elite or landed gentry (like the seigneurs).

life-course: A way of understanding and studying the lives of people in history by highlighting changing contexts, needs, abilities, and roles at different points in life.

Mechanics’ Institutes: Centres for adult literacy education, debate, and access to reading materials.

middle class: Also called the bourgeoisie. Ranks include liberal professionals, small merchants, and educators. Distinct from the the working class (who subsist on wages) and the upper class (whose wealth derives mainly from property and position).

nativism, nativist: The privileging of established residents over newcomers. Nativists take the position that their own rights are greater than that of immigrants because they have been resident longer (though sometimes not for very much longer).

normal schools: Teacher training institutions.

nuptiality: The incidence of marriage in a population.

Oddfellows: One of the oldest benevolent or friendly societies. May have sprung out of the guild movement. The Oddfellows developed personal and medical insurance schemes for their members.

Orange Lodges, Orange Order: Founded in the 1790s in Northern Ireland, a severely anti-Catholic fraternal society that advances the privileges of Protestants. Characterized as well by its loyalty to the Crown.

philanthropist, philanthropy: Equates very closely to charity, though on a significant scale. A philanthropist is someone with sufficient wealth to engage in charitable works.

proletarianized: The deskilling of work and work processes.

public houses, pubs: Facilities providing food, drink, and often a place to stay.

public markets: A space — sometimes a structure — built by the local municipality to provide for the sale of farm and food products.

respectability: A notion of moral character. As new social class structures took shape in the 19th century the ideal of respectability gained importance as a way of offsetting snobbery.

scientific racism: A form of racism that relies on categorization of racialized qualities/traits and measures physiological and genetic features as a means of demonstrating inherent differences in intelligence, morality, and ability. Distinct from earlier forms of racism based on religious belief, for example, scientific racism gained popularity from the mid-19th century on.

single-industry towns: Often also company towns, communities in which one industry predominates and is even exclusive. Mining and other resource-extraction communities are often single-industry towns, but a concentration of productive capacity around textiles or metal manufacturing might also manifest the qualities of a single-industry town.

sweated labour: An industrial workplace in which the labour is hard, the hours long, and the wages low. Sometimes associated with piecework that might be completed at home and not in the factory itself.

temperance movement: A crusade to reduce or even end the consumption of alcohol. Became a widespread phenomenon during the 19th century with the increase of visible urban drunkenness. The movement was characteristically championed by middle- and upper-class women.

total fertility rate (TFR): The number of births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 45 per year.

voluntary family size limitation: Also referred to as “birth control.” The attraction of building smaller families grew in the 19th century as the wage-earning potential or economic potential of children declined.

voluntary associations: See benevolent societies.

Short Answer Exercises

- How did economic change impact British North American society?

- What were some of the main features of the demography of British North America?

- What were the main sources of immigration? What impact did newcomers have on British North American society?

- In what ways did life in rural British North America change?

- What were some of the new features of 19th century cities? What were their principal challenges considered to be?

- Why did the mid-19th century see a sudden increase in the creation of institutions like universities, asylums, orphanages, and prisons?

- What were the principal social classes and groups to be found in British North America at mid-century?

- In what ways were social and economic roles gendered?

- How did sectarian violence and racism become part of the fabric of British North American culture and life?

- What was the role of formal education in the mid-century? What were its goals?

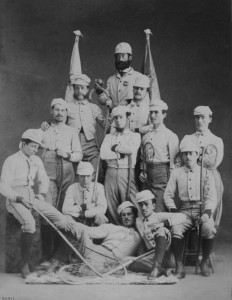

- How was leisure time understood at mid-century? How did organizations and associations figure into recreation?

Suggested Readings

- Bradbury, Bettina. “Widows’ Votes.” In Wife to Widow: Lives, Laws, and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Montreal, 260-288. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011.

- Olson, Sherry. “Ethnic partition of the workforce in 1840s Montreal.” Labour/Le Travail 53 (Spring 2004): 159-202.

- Prentice, Alison. “Upper Canada at Mid-Century: The Necessity of Progress.” In The School Promoters: Education and Social Class in Mid-Nineteenth Century Upper Canada, 45-65. Toronto: University of Toronto, 2004.

- Radforth, Ian. “Collective Rights, Liberal Discourse, and Public Order: The Clash over Catholic Processions in Mid-Victorian Toronto.” Canadian Historical Review 95, no.4 (December 2014): 511-44.

- Winder, Gordon M. “Trouble in the North End: The Georgraphy of Social Violence in Saint John, 1840-1860.” Acadiensis XXIX, no.2 (Spring 2000): 27-57.