Figure 2.8 Mound-builder societies produced functional and graceful structures, including the Great Serpent Mound in the Ohio Valley.

Early in their encounters with Aboriginal peoples, European newcomers struggled to conceive of and understand a continent teeming with (what was to them) mysterious peoples with highly unusual ways of doing things. Often the Europeans rejected the possibility that these civilizations could have arisen independently of Europe or Asia. Where the evidence to the contrary was inconvenient to their own worldview, Europeans sometimes simply stopped seeing it. Consequently, the myth developed that pre-contact Aboriginal societies were unsophisticated, unchanging, and primitive. This suited the newcomers’ agenda, but it was nothing like the truth.

Early Agriculturalists in the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys

The southeastern portion of North America was an early centre of agricultural development that fostered the growth of a large, long-lasting, and influential culture known as the Mississippian (ca. 500-1400 CE). This culture originated in the Mississippi River Valley and spread out to encompass an area that includes the lower Great Lakes region to the north, the Carolinas to the east, and northern Florida to the south. This culture emerged from the late Woodland Period as a significantly more sedentary culture of large-scale, corn-based agriculture. Surplus agricultural production allowed Mississippians to stave off famines and sieges, support a dense population that included a large group of specialized artisans, and engage in trade with non-farming neighbours.

Politically, Mississippians were organized as a chiefdom, a form of organization based on a hierarchy of chiefs that followed the leader of the most important group. Within the chiefdom existed a high level of social stratification, with a noble class at the top. Socially, the Mississippians appear to have practised matrilineal descent patterns, meaning that familial relations focused on the mother’s family, with property, status, and clan affiliation being conferred through the female line. A person’s most important relations were his or her mother’s parents and siblings; the father’s relations were relatively unimportant. Boys looked to their mother’s brother as an important male figure rather than to their father, and uncles passed political power and possessions to their nephews and maternal relatives rather than to their sons. This system’s main advantage is that descent and clan affiliation were beyond doubt; a child’s paternity may be uncertain, but a clan can be sure of a child’s maternity. Matrilineality is relatively common among indigenous peoples of North America (though it is not universal), and it may explain the important roles that women often played in Aboriginal political systems. (Note that this is not, however, the same thing as matriarchy, which is a political system in which authority resides with females. Nor can it be assumed that the Mississippians were matrilocal, which means that married couples reside in or in close proximity to the family/parents of the wife.[footnote]As one author writes, “Kinship and residence in Mississippian societies have been more assumed about than understood.” Patricia Galloway, “Where have all the Menstrual Huts Gone? The Invisibility of Mentrual Seclusion in the Late Prehistoric Southeast,” Reader in Gender Archaeology, eds. Kelly Hays-Gilpin and David S. Whitley (Oxford: Routledge, 1998): 197-211.[/footnote])

The religion practised by the Mississippians is known as the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Important religious symbols included a snake (sometimes depicted as a horned serpent), a cross-in-circle motif, and a warrior-falcon hybrid. These symbols were closely related to cosmology and to elites and warriors, giving the religion a socio-political aspect that reinforced the social status and authority of the elite — including the high chieftain, lesser chiefs, and the priests. In time, elements of this iconography found their way across much of southern Canada.

One key feature of the Mississippian culture was that they were mound builders. They produced thousands of earthworks used in a variety of manners, including burial mounds for the elite. The chief, his family, and perhaps other members of the chieftain class lived atop some of the mounds in longhouses. Other mounds — some of the largest — appear to have been centres of worship or temples.

The largest and most important Mississippian centre was Cahokia (ca. 600-1400 CE) located just across the Mississippi River from what is now St. Louis, Missouri. Cahokia was a walled complex made up of 120 mounds that housed perhaps as many as 30,000 people, making it a very large city for its day, certainly as large as contemporary Lisbon, Portugal. It had many of the features one would look for in contemporary towns and cities anywhere, including community plazas, which were located throughout the complex. A woodhenge (a circle of wood posts) was built for astrological observations, with poles in the henge marked to indicate the sun’s rising point on the solstices and equinoxes, making it a kind of community calendar or town-square clock. Cahokia’s mounds took tremendous effort to build; labourers moved about 1.5 million cubic metres of earth in their construction. The largest of the mounds, today called Monk’s Mound, is approximately 10 storeys high, covering an area of 5.6 hectares at the base. The top of the mound, the focal point of the city, housed a huge structure that may either have been a temple or the residence of the paramount chief of the Cahokia chiefdom.

Cahokia became a centre of power in part because of its location near the confluence of the Mississippi, Illinois, and Missouri Rivers. This confluence allowed the chiefdom to control much of the regional commerce, giving it access to a great variety of trade items from many regions. Cahokians participated in trade networks stretching as far as the Great Lakes to the north and the Gulf Coast to the south. The town began to decline around 1300 CE and slowly dwindled in size and importance, although some aspects of it remained in the 1500s. Scholars have speculated that overhunting, deforestation, a little ice age, and the rise of competing centres to the south contributed to Cahokia’s demise. The Ohio Valley, into which the French ventured in the 1600s and 1700s, carried many traces of the influence of the Mississippian culture; “Caouquias” appears on one of the first maps of the area, drawn in 1718 by Guillaume de L’isle. The Laurentian Iroquois of the St. Lawrence Valley and what is now southwestern Ontario (as well as the nearby Haudenosaunee or Five Nations Iroquois) would certainly have been influenced by this indigenous empire.

The Interior Plateau

A different model of high-density population in the pre-contact era is Keatley Creek, an important site above the Fraser Canyon in present-day British Columbia, which was well removed from the Mississippian and Mesoamerican cultures, which it mostly preceded. The Stl’atl’imx people who lived there from about 2800 BCE established an economy based on the salmon runs in the river below their plateau village. A large cluster of kekuli (pit houses) — as many as 115 house-sized depressions, the largest about 20 metres across — suggest a population of several hundred. Archaeologists cannot agree on the cause of its abandonment between 800 and 1,200 years ago. Old caricatures of Aboriginal societies as small, unsophisticated nomadic hunter-gatherer societies are challenged and overturned by this kind of evidence. It also provides a challenge to the model of agriculture-led town development. Keatley Creek in this respect has more in common with the Norte Chico culture of Peru (with which it was contemporary) that it does with Cahokia. Like the Mississippian tradition, Keatley Creek was a source of cultural diffusion and would have influenced many of its neighbours — by example or by force.

The Pre-Contact Era

The two centuries before the arrival of French exploratory missions in the 1530s witnessed enormous changes in Aboriginal North America. The “little ice age,” beginning in the late 1200s, had severe impacts on farming communities. From the middle of the 14th century there was widespread abandonment of the Mississippian cities and villages, and the archaeological record reveals extensive evidence of famine and dispersal of populations. Much of the desperate and violent conflict that took place between Iroquoian peoples of this period — and the peace between the Five Nations that eventually emerged — has been ascribed to the unsettled environmental conditions of the time.

The Plains

Westward and northward movement of horticulturalists and farmers brought new populations into what is now southern Manitoba and Alberta. Some may have attempted to recreate the semi-urban environment of previous Mississippian generations as far north as the Bow River. Others introduced maize farming near the Red River and the Tiger Hills, with limited success.[footnote]James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: U of R Press, 2013).[/footnote] Just below the 49th parallel on the Great Plains were more successful agriculturalists. Among the most important of these was the Mandan, whose villages along the Missouri and Knife Rivers survived until the smallpox catastrophe of the 1830s. Like many of their Siouan-speaking relations, they migrated into the region from areas associated with the Mississippian cultures. The Mandan villages acted as the commercial hub of an enormous wheel of Plains culture, one that extended into the lowlands around Hudson Bay. It included, as well, peoples who engaged in some corn farming and the harvesting of wild rice in what is now southern Manitoba and the western Lake Superior lowlands. The more nomadic peoples of the Plains in this period hunted large game, pursuing the herds on foot before the return of the horse in the post-contact period. Dogs pulling travois were an important asset; sometimes wolves were put to the same task. The Lakota, Cree, Assiniboine, and, further west, the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot), Shoshones, Gros Ventre, and Kutenai were participants in this shared Plains culture, as were later arrivals the Anishinaabeg (also called Plains Ojibwa or Saulteaux).

Although the hunting economies of Plains peoples evolved in many respects over the 8,000 years before contact, there were also some remarkable continuities. One of these is the buffalo jump phenomenon. Some 12,000 sites have been identified in Alberta alone, with the best known today being Head-Smashed-In (not far from present-day Lethbridge), which first came into use about 5,700 years ago. Buffalo jumps were kill sites, where herds of bison were driven off steep cliffs. If the fall didn’t crush their skulls or necks outright, they would be sufficiently stunned to allow for slaughter by hunters. The bodies would then be dragged to a nearby campsite and processed; every part of the animal was used to provide clothes (the hides), tools (the bones), and bowstrings (the sinew). Head-Smashed-In was in use for thousands of years, into the historic period, when Blackfoot, disguised as coyote and wolves, would drive buffalo along established “drive lanes” to the cliff. Excavations at Head-Smashed-In have unearthed a deposit of skeletons, primarily of bison, measuring more than 10 metres deep. But Head-Smashed-In is only one of many jump sites that dot the Prairies; another is Clay Banks Buffalo Jump in southwestern Manitoba, which was used by the Sonata and Besant cultures as early as 2,500 years ago.[footnote]Olive Patricia Dickason, “A Historical Reconstruction for the Northwestern Plains,” in The Prairie West: Historical Readings (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1992): 51.[/footnote]

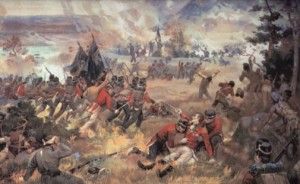

Warfare was endemic on the Plains. War was waged for three main reasons: to gain prestige, to obtain goods, and for revenge. The strategy and tactics of Plains warfare revolved around the concept of counting coup.[footnote]Anthony McGinnis, Counting Coup and Cutting Horses: Intertribal Warfare on the Northern Plains, 1738-1889 (Evergreen, CO: Cordillera Press, 1990).[/footnote] Coup was an action that demonstrated bravery and skill. The most highly valued coup was to touch a live enemy and live to tell about it. Killing an enemy was coup, too, but demonstrated valour to a lesser degree; after all, the live man is still a threat, while a dead one can do no harm. Touching a dead enemy was also a lesser form of coup. After a battle, warriors returned to the settlement to recount their stories, or “count coup.”

Religious beliefs on the Plains tended to hold the bison as a central figure of the sacred Earth. Most groups kept “medicine bundles,” a collection of sacred objects holding symbolic importance for the group. Often, religious celebrations centred on the medicine bundle. The concept of annual world renewal was an important one in Plains religion, and one of the chief renewal ceremonies celebrated by many Plains peoples was the sun dance. The sun dance was sponsored by an individual who wished to give to his tribe or to thank or petition the supernatural through the act of self-sacrifice for the good of the group. Celebration of the sun dance varied in detail from group to group, but a general pattern existed. It usually occurred in the summer and involved erecting a large structure with a central pole, symbolizing the Tree of Life. Large groups would gather to give thanks, celebrate, pray, and fast. The individual sponsoring the sun dance would pray and fast throughout the celebration, which lasted up to a week. He was the celebration’s lead dancer, and the dance would continue until his strength was completely gone. Often, the dance involved some kind of bloodletting or self-torture. Participants might pierce their skin and/or chest muscles and attach themselves to the central pole by piercing pegs and lengths of leather, dancing around or hanging from it until the pegs were pulled free. Another variation involved piercing the muscles of the back and dragging buffalo skulls behind the dancer until the weight of the skull ripped the pins out of the dancer’s flesh. The scars that the dancer carried after the celebration were a mark of honour. At the end of the sun dance, the world was renewed and replenished.

The East

Northeastern Aboriginal peoples were diverse and complex in many respects. Economically, they relied on both hunting-gathering and farming, as well as trade. Iroquoian-speakers — the Wendat (Huron), Tionontati (Pétun or Tobacco), and Attawandaron (Neutral) of southwest Ontario and the Laurentian Iroquois (which included the people of Stadacona and Hochelaga), as well as the Erieehronon (Erie), Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk, Seneca, and Cayuga, whose territories were south of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence — built their societies around the planting and harvesting of the “three sisters” (corn, squash, and beans). Farming led to larger population numbers, bigger villages, more elaborate political structures to manage internal decision making and diplomacy (or war), and the capacity to store large quantities of surplus crops in the event of famine and for trade purposes. The 500 years before contact were marked by political transformations that produced confederacies and leagues among the Iroquoians, the most successful and largest of which were the Haudenosaunee (also known as the League of the Tree of Peace and Power, or the Five Nations Iroquois) and the Wendat Confederacy. These alliances were an effective means of reducing the prospect of long-running blood feuds between many bands and clans, although the creation of confederacies may have simply increased the scale of warfare between a few larger groupings.

The other eastern peoples were mostly Algonquian-speakers. These include the Abenaki, Mi’kmaq, and Maliseet (subsequently known as the Wabanaki Confederacy) in what are now the Maritimes and much of modern New England; the Innu (also known as Montagnais) on the north shore of the St. Lawrence and in the north-central Ungava Peninsula; the Nippissing (whose lands surround the lake bearing their name); and the three closely aligned factions of the Anishinaabe group: the Algonquin, Odawa, and the Ojibwe. The existence of Algonquian alliances hint at conflict with others; many of these peoples shared a common dislike of the Iroquois long before the arrival of Europeans. Several claim to have driven them westward out of the northeast and the Gaspé and perhaps out of the St. Lawrence Valley in the years before contact and shortly thereafter. Principally foraging horticulturalists, these Algonquian-speaking peoples were highly mobile. They made extensive use of the resources of the land and the sea, with the Mi’kmaq establishing an eastward position in southern Newfoundland.

All peoples of the northeast participated in extensive networks of commerce. Many participated in a system of exchange with shells (sometimes called “wampum”). The shells, which themselves were highly valued, had a currency value but were often assembled in strings, on belts, and otherwise in patterns that served as mnemonic devices to record the details of treaties or other agreements. Similarly the Mohawk — whose homeland was along the Hudson River in what is now New York State but who are now mostly settled in Ontario and Quebec — were noted traders in flint, a commodity that made them wealthy and powerful, not least because it was used as part of the Aboriginal arsenal.

Warfare played an important role in the northeast as it did on the Plains. It was the chief way to gain power and prestige, and revenge was its primary driver. A cycle of war was ensured because each group sought to avenge those killed in earlier wars or skirmishes in what became called the Mourning Wars. Acceptable outcomes of war could take several forms: killing the enemy, taking captives, and taking trophies of some sorts, often in the form of beheadings and/or scalping (a practice that may have been introduced to the region by Europeans). Captives would be taken back to the victors’ town, where they would be handed over to the women who had lost family members to war. Ultimately, one of two fates awaited a prisoner: either being tortured to death (which could last many hours or even days) or being adopted by one of the families whose warrior-males had died in battle or were prisoners themselves. The captive who withstood the torture by showing strength and singing his “death song” so as to have a good death, would be held in high esteem and sometimes spared. Occasionally, the torturers would consume the flesh of those tortured after they had died, in order to ingest the strength of the enemy, a practice that many cultures shared. At the very least, Iroquoian and other cultures echoed sacrificial practices conducted on a large ritualistic scale by the Aztec and Mayan peoples.

The Beothuk may have been an exception to many of these models and cultures. What little is known about these original inhabitants of Newfoundland and Labrador is discussed in Chapter 7. One distinctive element of their culture that would have a lasting impact on European perceptions of Aboriginal peoples was their practice of liberally applying red ochre over their bodies. It was this custom that led to newcomers describing them as “red Indians,” an appellation that wound up being much more broadly used.

People of the Far Northwest

The Pacific Northwest region was utterly separate from the Plains and other cultural zones. Its peoples were many and they shared several cultural features that were unique to the region.

By the 1400s there were at least five distinct language groups on the West Coast, including Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Wakashan, and Salishan, all of which divide into many more dialects. However, these differences (and there are many others) are overshadowed by cultural similarities across the region. An abundance of food from the sea meant that coastal populations enjoyed comparatively high fertility rates and life expectancy. Population densities were, as a consequence, among the highest in the Americas.

The people of the Pacific Northwest do not share the agricultural traditions that existed east of the Rockies, nor did they influence Plains and other cultures. There was, however, a long and important relationship of trade and culture between the coastal and interior peoples. In some respects it is appropriate to consider the mainland cultures as inlet-and-river societies. The Salish-speaking peoples of the Straight of Georgia (Salish Sea) share many features with the Interior Salish (Okanagan, Secwepemc, Nlaka’pamux, Stl’atl’imx), though they are not as closely bound as the peoples of the Skeena and Stikine Valleys (which include the Tsimshian, the Gitxsan, and the Nisga’a). Running north of the Interior Salish nations through the Cariboo Plateau and flanked on the west by the Coast Mountain Range are societies associated with the Athabascan language group. Some of these peoples took on cultural habits and practices more typically associated with the Pacific Northwest coastal traditions than with the northern Athabascan peoples who cover a swath of territory from Alaska to northern Manitoba. In what is now British Columbia, the Tsilhqot’in, the Dakelh, Wet’suwet’en, and Sekani were part of an expansive, southward-bound population that sent offshoots into the Nicola Valley and deep into the southwest of what is now the United States.

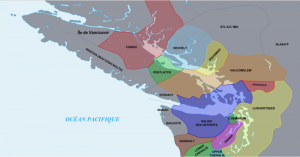

Figure 2.11 The Salish Sea (as Georgia Strait is now widely known) was an ecologically and culturally rich zone occupied by related but unallied peoples.

Most coastal and interior groups lived in large, permanent towns in the winter, and these villages reflected local political structures. Society in Pacific Northwest groups was generally highly stratified and included, in many instances, an elite, a commoner class, and a slave class. The Kwakwaka’wakw, whose domain extended in pre-contact times from the northern tip of Vancouver Island south along its east coast to Quadra Island and possibly farther, assembled kin groups (numayms) as part of a system of social rank in which all groups were ranked in relation to others. Additionally, each kin group “owned” names or positions that were also ranked. An individual could hold more than one name; some names were inherited and others were acquired through marriage. In this way, an individual could acquire rank through kin associations, although kin groups themselves had ascribed ranks. Movement in and out of slavery was even possible.

The fact that slavery existed points to the competition that existed between coastal rivals. The Haida, Tsimshian, Haisla, Nuxalk, Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv (Oowekeeno), Kwakwaka’wakw, Pentlatch/K’ómoks, and Nuu-chah-nulth regularly raided one another and their Stó:lō neighbours. Many of the winter towns were in some way or other fortified and, indeed, small stone defensive sniper blinds can still be discerned in the Fraser Canyon. The large number of oral traditions that arise from this era regularly reference conflict and the severe loss of personnel. Natural disasters are also part of the oral tradition: they tell of massive and apocalyptic floods as well as volcanic explosions and other seismic (and tidal) events that had tremendous impacts on local populations.

The practice of potlatch (a public feast held to mark important community events, deaths, ascensions, etc.) is a further commonality. It involved giving away property and thus redistributing wealth as a means for the host to maintain, reinforce, and even advance through the complex hierarchical structure. In receiving property at a potlatch an attendee was committing to act as a witness to the legitimacy of the event being celebrated. The size of potlatching varied radically and would evolve along new lines in the post-contact period but the outlines and protocols of this cultural trademark were well-elaborated centuries before the contact moment. Potlatching was universal among the coastal peoples and could also be found among more inland, upriver societies as well.

Horticulture (the domestication of some plants) was another important source of food. West Coast peoples and the nations of the Columbia Plateau (which covers much of southern inland British Columbia), like many eastern groups, applied controlled burning to eliminate underbrush and open up landscape to berry patches and meadows of camas plants that were gathered for their potato-like roots. This required somewhat less labour than farming (although harvesting root plants is never light work) and it functioned within a strategy of seasonal camps. Communities moved from one food crop location to another for preparation and then, later, harvest. A great deal of the land seized upon by early European settlers in the Pacific Northwest included these berry patches and meadows. These were attractive sites because they had been cleared of huge trees and consisted of mostly open and well-drained pasture. Europeans would see these spaces as pastoral, natural, and available rather than anthropogenic — human-made — landscapes, the product of centuries of horticultural experimentation.

Summary

More than 500 identifiable groups emerged in North America during the pre-contact era (that is, from 1000 to 1492 CE). Although tremendously diverse, the groups within each region of the continent shared many common features, including subsistence strategies, kinship relations, political structure, and elements of material culture. And although there were common economic and cultural features across North America and some that were shared in Meso-America and South America as well, this does not in any way indicate a single monolithic Aboriginal culture. In the northern half of North America alone the number of tongues spoken, artistic techniques perfected, songs and dance styles, architectural and engineering experiments, and systems of government can barely be calculated.

Nomenclature

“Nomenclature” is the word used to refer to a set or system of names used in a particular field of study. How do we name things? Which names are correct? Some terms fall out of favour while others rise. In the study of Aboriginal history, this is particularly important.

- Indians: The term used by newcomers (not by native peoples) to describe and characterize all the Aboriginal peoples of the Americas. Aboriginal peoples today sometimes describe themselves as Indians, though generally in a political context. The Canadian Indian Act, for example, uses the word “Indian” to describe native peoples, as do some native organizations (e.g., the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs). Keep in mind, of course, that there is no singular “Indian” culture, no one “Indian” language, no universal “Indian” economy. Making that assumption is an error referred to as “pan-Indianism,” the mistaken belief that all Aboriginal societies are essentially the same. The diversity of Aboriginal cultures, languages, and economies was a fact in the past and remains a fact today.

- First Nations, Amerindians, American Indians: Beginning in the mid-20th century, Aboriginal peoples and non-Aboriginal peoples began experimenting with terms to replace “Indian.” In Canada, the term that has so far enjoyed the widest use and recognition is “First Nations.” “First Peoples” is also used, as is “indigenous peoples” and “Aboriginals.” In the United States the most widely used terms are “Native Americans” and “American Indians,” sometimes contracted to “Amerindians.” This last term is sometimes embraced by Aboriginal peoples as being the most serviceable.

- Nuxalk, Anishinaabe, Wendat, Mi’kmaq: As 20th-century Aboriginal peoples found a stronger political voice, many articulated a desire to be known by their own nation names. Bella Coola became Nuxalk, Ojibwa became Anishinaabe (Anishinaabeg is the plural form), Huron reverted to Wendat, and Micmac reacquired a breath in the first syllable and a more open consonant at the end of the second in the form of Mi’kmaq. These are only four examples. Across the country Aboriginal peoples are reclaiming their names, an important step toward reclaiming their history.

Key Points

- Elaborate agricultural societies with some measure of urbanization appeared in the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys around 500 CE and began to decline in the century or so before contact with Europeans.

- High density communities arose around the same time, based on maritime and riverine food resources.

- Pre-contact societies included hunter-gatherers, farmers, and seafaring mammal hunters, all of whom were engaged in commerce.

Attributions

Figure 2.8

The Great Serpent Mound, courtesy of Richard A. Cook/Corbis, is in the public domain. This image is available from the U.S. National Library of Medicine website.

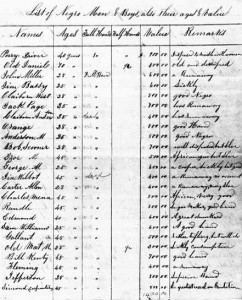

Figure 2.9

Views of the remains of a mound at Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, courtesy of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, is in the public domain. This image is available from the U.S. National Library of Medicine website.

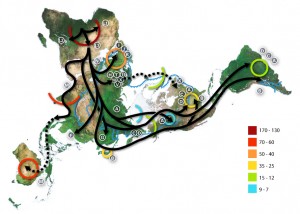

Figure 2.10

Mississippian cultures HRoe 2010 by Ras67 is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.

Figure 2.11

The Salish Sea by Arct is used under CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.