The Iberians

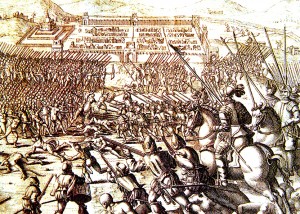

Three decades after Columbus’s voyages, the Spanish were in control of a vast quilt-pattern of indigenous empires. Their military prowess had been sharpened in the reconquista and their tolerance for non-Catholics dulled by the Inquisition. The colonization of Cuba began in 1511 and from there the attacks on Mexico began. In 1518 a small force led by the conquistadore Hernán Cortés began the process of conquering the Mayan city states of the Yucatan, then liberating tribute-paying provinces of the Aztec Empire (which sent 200,000 of their own troops against the Aztec capital). Smallpox was Cortés’ other, hidden ally and it would kill thousands upon thousands, enabling a Spanish victory. In 1521 the Aztec capital fell and the Spanish took on the administrative mantle of the ousted regime.

Similarly, a conquistadore mission under Francisco Pizarro (ca. 1476-1541) made three attempts on the Incan Empire of Peru. Pizarro succeeded in 1532 after holding the last Sapa Inca, Atahualpa, hostage for ransom and then executing him. Again, the Spanish appropriated the indigenous administrative structure and many of its legal practices, adapting some while replacing others. This system of conquest allowed the Spanish to take advantage of existing labour supplies and to easily divert local wealth to Spain. The Spanish Crown clearly had an interest in this process and quickly began centralizing its control of the new territories.

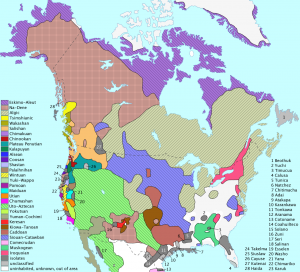

In 1524 the Spanish Council of the Indies was created, and New Spain was divided into four viceroyalties. One of these, also called New Spain, would play a role in the geopolitical struggle for North America, as it included Mexico and Central America, gradually extending into California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. Its wealthy capital was Mexico City (the former Tenochtitlan).

The economic systems of Spanish America were also strictly controlled hierarchical and economic endeavours. Native labourers were provided through the encomienda system, which was a grant from the king given to an individual mine or plantation (hacienda) owner for a specific number of natives to work in any capacity in which they were needed; the encomenderos, or owners, had total control over these workers. Ostensibly, the purpose was to protect the natives from enemy tribes and instruct them in Christian beliefs and practices. In reality, the encomienda system was hard to distinguish from chattel slavery. The repartimiento, which granted land and/or indigenous people to settlers for a specified period of time, was a similar system.

In the Portuguese territory of Brazil, economic development centred on sugar rather than silver and gold. As the Europeans subdued local populations, increasing numbers of sugar plantations emerged along the Atlantic coast. Most of the labour on the sugar plantations came from native slaves, though they aggressively resisted control by the Europeans. In fact, many of the plantations failed in part because of the resistance of the natives. Vulnerability to imported diseases was a further factor, reducing the viability of enslaving Aboriginal peoples. By 1600, Africans, who had developed immunity to European diseases over centuries of interaction between the two continents, were replacing indigenous peoples as slaves on the sugar plantations. Around the same time, African slaves found themselves shipped to the Pacific coast of South America where thousands worked in silver mines, such as the gargantuan operation at Potosí in Peru (now southern Bolivia).

This was the beginning of what became understood as triangular trade. European ships sailed to African slave markets, purchased large numbers of humans whose lives were to be given over to hard labour in the fields, shipped them across the Middle Passage (during which time huge numbers died), and sold them to plantation owners. Sugar and other crops, as well as mineral wealth, were then loaded onto ships, which promptly made the return trip to European markets and merchants. This model and variations on it would inform every colonial enterprise in North America and is explored in Chapter 6.

Countermove: The Dutch

Because Spain and Portugal were the first to found colonies in the Americas, the patterns they established served as the template for other European empires. The biggest challenges that they faced in administering their colonial holdings were those of time and space. Communication between colony and the imperial centre was difficult, and it took months for messages, orders, and news to travel across the Atlantic. The distance between Europe and the Americas played a very important role in shaping colonial administration along with patterns and methods of imperial control. The ways in which the Iberian powers politically and economically administered their colonial holdings were also a reflection of the relationship between “mother country” and colony: the American holdings were settlement colonies shaped in the image of Spain and Portugal. Spaniards and Portuguese set up a direct system of governance that exerted tight control over the colonies just as absolutist monarchies at home tightly governed their own people. The Spanish and Portuguese colonies benefited the mother country economically and colonial trade was tightly controlled. This was the model that the Dutch and other European intruders in the Americas sought to emulate.

However much they wanted successful colonies, the Dutch also wanted to weaken the Spanish (and to a lesser extent, the Portuguese) hold on the Americas. This created a dual focus for the Netherlanders: build and disrupt. The Dutch concentrated on weakening their Spanish competitors through piracy in the Caribbean, something for which they seemed to have a true knack. As for the Portuguese, the Dutch took them on more directly, conquering small but important lands in Brazil. Ignoring the Treaty of Tordesillas, the Dutch established a colony on the Hudson River around 1614 and held onto that position until the 1660s. Their colonial economy was a mixed one, but one aspect — the fur trade with the Haudenosaunee — would bring the Dutch into conflict with New France.

Key Points

- Spain’s first emissaries to the Americas were reconquista-hardened soldiers whose understanding of war was as a means of obtaining plunder, power, and religious conformity.

- Spain’s influence spread swiftly throughout Mesoamerica and along the Pacific coast of South America.

- The model of colonialism and imperialism developed by the Iberians would inform the decisions made by the Dutch, English, and French in North America.

Attributions

Figure 3.7

Cusco battle by Noh-var 2 is used under a CC-BY-SA 3.0 license.