This site is a test-run of downloading and importing an open textbook from BCcampus. The material uploaded but the structure is not usable right away.

-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

Archives

Categories

Meta

This site is a test-run of downloading and importing an open textbook from BCcampus. The material uploaded but the structure is not usable right away.

Dedicated to the memory of Mr. George Porges (d.2004), whose introductory History courses at Douglas College were truly inspired.

To what extent is it possible to think of children in past centuries as having agency in their own lives? Feminist historians have corrected the widespread misconception that women were mere shadows in the past; historians of First Nations have likewise shown that Aboriginal people were actors and not merely acted upon. Post-colonial and feminist critiques have moved those goal posts — can the same be done for the history of childhood?

Certainly children faced constraints in past societies. Paternal authority in law was unquestioned in both French and English civil and common law; children had no independent rights whatsoever. What’s more, as property, they were able to be reassigned to other owners, whether temporarily (as in the custodial care of an orphanage) or permanently (as in “binding” as an apprentice to a master or to the navy). Children who had become impoverished and thus dependent on the state or parish could be bound by either to an employer/master. In instances like these the permission of parents wasn’t needed. For the least fortunate in Upper Canada, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland, the British Poor Laws applied. Boys and girls were mixed in with adults of all ages in circumstances that provided them little in the way of safety from harm. An 1832 inquiry into the Halifax Poor Asylum revealed “that the seventy-four orphan children in the institution slept with adults ‘without any regard to fitness of health or morals.’” Conditions did not improve in a hurry: in 1849 it was discovered that boys and girls — some as young as eight years old — were regularly whipped with rawhide while incarcerated at the Kingston Penitentiary.[footnote]Robert McIntosh, Boys in the Pits: Child Labour in Coal Mines (Montréal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000), 29-30.[/footnote] There is no doubt, then, that children were vulnerable and frequently exploited and harmed.

But that is not the same thing as being powerless or without influence. The discourse around the rise of “street arabs” is clear about one thing: urban adults felt menaced by children. That is not to say that street children were a force for chaos and danger, but that they resisted the self-appointed moral authority of the state and adults. Faced with dangers themselves, children often found strength in groups of peers and they resisted institutionalization. They fled and taunted; they spoke up for one another. Solidarity occasionally occurred.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence of childhood agency comes not from the emerging cities of the early Victorian era but from Wendat society before the Confederacy’s disruption in 1649-50. Ceramics was an important part of the cultural and artistic life of the Wendat. As a non-nomadic farming people, the Wendat had both the capacity to store large numbers of ceramics and had many uses for containers. Ceramic production was, therefore, a central part of village life. An archeological study from 2006 demonstrates that children were involved in the making of pottery variously known to scholars as “juvenile,” “baby,” or “toy” ceramics. “These small ceramic vessels are … categorically different, in formation and design from the typical, widespread ‘adult’ pots.” What a careful examination of these artifacts reveals is that children were not merely learning the art of ceramics: they were introducing stylistic change.[footnote]Patricia E. Smith, “Children and Ceramic Innovation: A Study in the Archaeology of Children,” Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 15 (2006): 65.[/footnote] Childhood creativity, invention, and innovation were forces for change within pre-contact Wendat societies and, we can safely assume, in all those societies that followed.

Figure 12.4

Curling on the lake, near Halifax, NCurling on the lake, near Halifax, Nova Scotia by Library and Archives Canada is used under a CC-BY 2.0 license. This image is available from Library and Archives Canada under the reproduction reference number C-041092.

Figure 11.4 Government House, Halifax, 1819, the home of the governor and thus the seat of government for the colony.

The history of politics is like a sausage that can be sliced several different ways.[footnote]The German militarist and politician Otto von Bismarck famously made the connection between politics and ground meats when he said, “Laws are like sausages, it is better not to see them being made.”[/footnote] One way is to look at the politicians of the day, the prominent figures who led the debates around policy and strategy. Personality matters as a force in history and we cannot know the contexts of decisions made without knowing something about the players.

Another way is to look at power itself, which is ultimately the business of politics. Where did power reside in this society and why? What forces were being mobilized that would raise or ruin the likelihood of this group or that having more agency in making their own history? It’s not enough to say, for example, that women had little political power because they couldn’t vote; they couldn’t vote because their power itself was limited, and we need to understand why.

There is, as well, the question of ideology to address. What ideas and values drove people in their struggles for power? This relates, too, to the language of politics: words like democracy and freedom clearly have meanings that change over time. As heirs to a long tradition of liberal democracy, we need to appreciate that its practices came into being as part of a movement, and that those who advocated greater democracy in one generation might have been appalled at where those changes went in the next.

Finally (and this is not an exhaustive list of topics), there is the media to consider. As the colonies became larger and more complex, the influence of the press also grew. It isn’t just the case that we should pay attention to what journalists had to say; we need to know what it was that newspapers were trying to be in the 19th century.

With economic and social change after 1818 came demands for political transformation. An oligarchy with roots deep in the pre-Conquest soil of Canada and New England was at odds with a rising bourgeois class in the towns and cities. In an age defined by new theories of social relations and power, by the rise of democratic and socialist ideas in England, and by technological advances that sped up communications, people across British North America debated change: should it come and, if so, how much and how fast?

Not all of the colonies of British North America were governed similarly. It is true that their constitutions derived from a combination of American traditions and practices, on the one hand, and British parliamentary models on the other. Loyalist refugees brought with them a powerful expectation of continuity of American practices in the Maritimes as British colonies appeared there after 1713, and many believed the absence of a local assembly in Nova Scotia deterred some potential migrants from New England, at least until 1758. Cape Breton (independent of Nova Scotia until 1820) never had its own representative assembly, nor did Newfoundland until 1832. Tension between Catholics and Protestants in Newfoundland reached such a pitch mid-century that half of the seats in the colonial assembly were stripped from the electorate and filled with appointees. Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick both inherited much of their administrative structure from Nova Scotia, to which they were both for a time attached. Prince Edward Island’s assembly was made problematic by the landholding system on the island: most of the landowners were absentees. This and tenant-farmer unhappiness put their assembly at jeopardy on several occasions.

Nova Scotia got its first elected assembly in 1758, but its ability to control government expenditures — money bills — was limited. The legislative council, an appointed body, was able to alter or amend legislation arising in the assembly, a practice that was unusual by British American standards and offensive to the New England element in the colony. It was, as well, out of step with Westminster’s ability to control expenditures. Nova Scotia in the late 18th century thus became a testing ground for all the constitutional issues that would face the rest of British North America in the years ahead.

By 1808 the Nova Scotia Assembly controlled much of the government’s spending. Executives, however, retained control of external revenue sources and that allowed them to spend money outside of the assembly’s purview. Political appointments and rewards were commonly used to secure support for the regime and for advancing the interests of the Church of England. These appointments were paid for through the “civil lists” — public appointments — over which all the British North American assemblies desired control. Governors and executive councils realized that assembly control of the civil lists would put an end to patronage and would undermine paternalism. In the 1830s a compromise was struck peacefully in the Maritimes in which the assemblies gained control over money bills (that is, legislation that involved expenditures) with the exception of the civil list.

Unlike the Canadas (which are considered in the next section), the Maritimes had no formal constitution until the 19th century. Reflecting the military orientation of the Atlantic outposts, the governors of these colonies were simply supplied with “instructions” from the Crown for the term of their appointment. Of course, these could be renewed or changed or rescinded over the course of a term in office.

All of the assemblies in British North America were elected. The extent of their authority varied over time and between colonies. The electorate also varied. Only property owners could vote and, since Catholics could not own property outside of a special dispensation, Acadians and Canadiens were initially not enfranchised. This soon changed in Lower Canada, but the law would stay in place in Nova Scotia until the 1820s. Further, elections were not conducted by secret ballot: they occurred in public view, providing opportunities for opposing sides to sway electors by means of drink, bribes, threats, and beatings. Only a small fraction of the adult population was able to vote in the pre-Confederation period and, outside of Lower Canada, the electorate was entirely male. Assemblies were sometimes split between advocates and opponents of deference to the governor. At times in the 19th century, individuals who wished to change the relationship between the governor and the assembly dominated the House; these individuals were called Reformers.

Legislative council: In Nova Scotia prior to 1758, the council was created as a committee to devise legislation for the governor. Its members were appointed from a network of local elites. More like Britain’s appointed and hereditary House of Lords than the House of Commons, the legislative council constituted the political upper class in the colony. With the introduction of assemblies, the council’s role changed to proposing and revising legislation that was debated by the assembly. It was this power of revision that some members of the assemblies most disliked, specifically as it applied to money bills.

While governors might be inclined from time to time to appoint into the legislative council someone drawn from outside the Anglican Tory elite, the executive was consistently an appointed body of the highest Tories and Loyalists. In Lower Canada their number were increasingly dominated by the Montreal fur-trading establishment and early capitalists. The executive was responsible only to the governor, but that didn’t stop them from biting the hand that fed them. Sir George Prevost (1767-1816), the governor of Lower Canada during the War of 1812, was effectively hounded from office by his own appointees.

The title of this position varies between governor, governor general, and lieutenant-governor. Defending Nova Scotia against the French or Upper Canada against the Americans was part of the job description. To deal with civil matters — everything from road construction to education, from civil order to land titles — governors appointed an executive council to provide oversight and a legislative council to write the laws. Governors were appointed by the Crown (in practical terms, the British cabinet). They came from three sources: most in the 18th century were high-ranking military men with battle experience; some of the early governors and more in the 19th century were from the British aristocracy; a few in the late 18th century were North Americans who cut their administrative teeth as governors in the Thirteen Colonies. All of them were Anglicans. Sir John Sherbrooke (ca. 1764-1830), the lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia from 1811 to 1816 and governor general of British North America from 1816 to 1818, for example, rose to the rank of Lieutenant General in the British Army. He was first sent to Nova Scotia to improve its defences and, later, to mount an attack on American territory. (Ironically, he was better as a civic administrator than as a military figure and made peace between difficult factions in Lower Canada in only two years.) Lord Durham and Lord Sydenham provide mid-century contrasts: the former was an aristocrat sent to British North America to referee the conflicts of 1837-38, and the latter was a commoner who had risen to political and bureaucratic prominence as treasurer of the Royal Navy (he lasted in Canada from 1839 to 1841).

Figure 11.4

The Government House in Halifax by WayeMason is in the public domain.

This textbook considers the history of what becomes Canada in 1867. It is what is called a “survey text,” in that it provides a framework of the larger storylines rather than examine in detail some particular aspect of Canadian history.

The thing is, what we survey is inevitably selective. Indeed, framing the story as something that leads to — or terminates at — Confederation is to suggest from the outset that there is a trail blazed from European arrival in North America to the creation of Canada. Telling the story that way is essentially flawed, from a historian’s perspective. It funnels the story to an outcome — to one outcome — as though there were no others along the way, or that other events — the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the War of 1812, the Rebellions of 1837 — wouldn’t work just as well as a bookend. And, obviously, when the terminus we choose happens to be a constitutional accomplishment of one group of Canadians — that is, those Canadians of European origin — we are implicitly overlooking the ongoing arc of the Aboriginal peoples’ story. It must be conceded that new political experiments are important, but one might as reasonably bring the tale to a pause with the onset of urbanization and industrialization, a social and economic process that redefined the lives of North Americans in the mid-19th century.

Canadian History: Pre-Confederation attempts to keep in view those other stories while visiting — and sometimes revisiting and reconsidering — familiar territory associated with the construction of what we call “Canada.” The text was conceived with an awareness of typical learner goals in undergraduate intro Canadian courses, an understanding that many student/users are likely to be newcomers to Canada and thus may not share in some common narratives, and a commitment to critical approaches. It is not a device intended to produce patriots or better citizens; it exists to acquaint people with issues in the past, to engage them with the experiences of others, to develop critical faculties, to become knowledgable about events and societies in North America, and to develop some of the skills of a historian. The foremost of these is empathy.

The text is organized in a roughly chronological fashion. Chapter 1 “When was Canada?” addresses historical methods and issues and then the text turns to communities and events and people in the past. The chronological approach is detoured beginning with Chapter 8 “Rupert’s Land and the Northern Plains, 1690-1870.” Chapters 9-11 consider, each in turn, the period from 1818 to ca. 1860 in terms of economic, social, and political histories. Chapter 12 “Children and Childhood” explores an aspect of social history from before the arrival of Europeans to the industrial age. Chapter 13 “The Farthest West” considers the territories west of the Rockies, much of which is now British Columbia; this chapter, too, plunges back in time to the mid-18th century. Chapter 14 “The 1860s: Confederation and Its Discontents” caps the chronological saga with an exploration of the processes that led to a federal union of colonies in July 1867. Confederation is a watershed: not only does it mark the beginning of a colonial nation-building exercise, it signals the transfer of authority over territory and peoples from London to Ottawa. While it is the case that international policy remained a matter for Westminster, from 1867 on Canada was setting its own diplomatic course with the other nations of North America, apart from the USA. Those “other nations,” of course, being the First ones.

Each chapter consists of several parts. These ‘subchapters’ are meant to facilitate the addition and subtraction of material from the OpenText format. Most are linked narratively, but not so much that one cannot be omitted or replaced without dire consequences.

Canadian History: Pre-Confederation includes several learning/teaching instruments. The first section (the x.1 of each chapter) includes Learning Objectives. These are, I think, consistent with what most introductory Canadian History courses hope to accomplish.

Almost all of the subchapters (apart from the Summary subchapters) conclude with a list of Key Points that are intended to help you identify themes that have overarching importance. But they are not exhaustive. There’s more in each section and it would be a mistake to think that the Key Points are all that matters.

The Summary sections conclude with three features: Key Terms, Short Answer Exercises, and Suggested Readings. Not all Key Terms are defined in the text body, but all words that are marked as bold in the body of the text are included in the Key Terms box. A Glossary at the very end of the text collects all of the Key Terms in one place. As regards the Suggested Readings, an effort has been made to ensure that everything listed is available online through your university library.

Clearly the definition of what constitutes a “key term” or a “learning outcome” is subjective. Choices have been made. The advantage of the OpenText format is that an instructor is encouraged to make different choices.

Scattered throughout the text are Exercises. These are intellectual tasks that are meant to help you develop a historians’ sensibility and awareness. They are not assignments (although they might be); they are opportunities to break from the narrative, to look up for a moment, and to see History around you. The are exercises meant to discipline and sharpen your mind just as push-ups improve your body. (Incidentally, it is a little known fact that all Canadian historians have six-pack abs.)

The names we use for people-groups in the past change over time. Sometimes that’s a result of changes in jurisdictions and borders or a constitutional change. Take “England” before 1701: it’s really England and Wales but it doesn’t include Scotland, which was a separate country; after 1707 “Britain” refers to all three together (along with Ireland) — the distinction is important. To take another example, New Brunswickers and Nova Scotians went to bed on 30 June 1867 and woke up the next morning in Canada. In this text an effort has been made to be consistent with identities as they were at the time. There’s no way that anyone at the forks of the Thompson and Fraser Rivers in 1808 could know that they’d be “British Columbians” fifty years later and it’s a fair bet that they would have been unhappy at the prospect as well. Even in 1858 very few British Columbians would have imagined that thirteen years later they would be “Canadians.” To push those labels backwards in time is to imply that people in history mysteriously knew an outcome that was not yet on the cards.

Names change, too, for political and cultural reasons. This is most obviously and importantly the case when it comes to Aboriginal group names. Almost universally in North America the names that people of European descent use to identify Aboriginal groups are not the ones First Nations themselves prefer. This situation began changing about thirty years ago and this text contributes to that process by employing nomenclature preferred by Aboriginal peoples. Why is it important to do so? Because most of those European-devised names are artifacts of colonial power or terms of disrespect. “Thompson Indians” is obviously not the name that the Nlaka’pamux gave to themselves. Some Aboriginal names, such as “Eskimo” in fact derive from negative, xenophobic epithets used by their neighbours and rivals. The term “Indian” itself is evidence of European confusion and ignorance, a reminder that 15th century travellers were hoping to reach India and not the Americas.

As a rule, then, the current nomenclature officially endorsed by the people themselves is used here. In the first usage (and where it seems appropriate to do so) the most well-known alternative is presented as well. For example: Anishinaabe (aka: Ojibwa); Wendat (Huron), Heiltsuk (Bella Bella). Some nomenclature offers several options and some of those are too useful to abandon. For example, the Haudenosaunee (aka: Five Nations Iroquois) are also known as the League of Five Nations, which works rather well in its own right.

Exceptions are made to these rules throughout the text for the Cree. The term “Cree” derives from French terms (Kristineaux , Kiristinous , Kilistinous) which may, themselves, be descended from names given them by their Aboriginal neighbours. The Cree in the pre- and proto-contact eras can be described as three cultures: Swampy, Woodland, and Plains. Each of these had a variety of alternate names. The Swampy Cree, for example, appear in European documents as West Main Cree and Lowland Cree and they describe themselves as Maskiki Wi Iniwak, Mushkegowuk, from which we derive Muskegon. There are eastern and western divisions within the Swampy Cree, which further complicates matters, as does migration across those two divisions. The Woodland Cree are similarly divisible between the Woods and the Rocky Cree, and nomenclature divides in this case between Sakāwithiniwak and Nîhithaw. The Plains Cree refer to themselves as nêhiyawak. Given the enormous territory in which the historic Cree were dominant — from the Rocky Mountains to Labrador — it is unsurprising to find significant differences in identities among these Algonkian-speakers, even at the dialect level. There is, however, a historic and pre-contact continuity across the Cree range and for that reason and to avoid confusion, the decision has been made to perpetuate the mis-label, “Cree.” For the purposes of understanding the different experiences of the fur trade in different eco-systems, the established modifiers survive as well: Swampy, Woodland, and Plains.

The past doesn’t explain the present. For the most part the past doesn’t even care about the present. What history reveals is complex and competing values and needs. How people dealt with those wrinkles and puzzles in the past demonstrates both their genius and their frailties. Those are the things we learn from the past and mostly they have to do with what it means to be human.

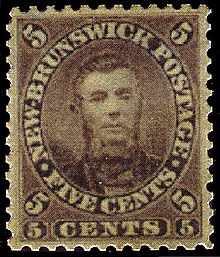

Figure 14.1 Images on stamps were common and widely shared representations of an emerging British North American identity.

In the 1850s and 1860s, cracks began to appear in the relationship between British North America and Britain. The 1859 New Brunswick stamp shown in Figure 14.1 makes two revealing breaks with imperial norms. First, its value is shown in cents, not British pence. Currency issues had plagued colonies in the West Indies and the rest of the British Empire for centuries, and there was no unity on this subject even among the colonies of British North America at mid-century. Second, the new postmaster for New Brunswick, Charles Connell, unsure of the shifting protocols, scandalously chose to put his own face on the stamp, rather than Queen Victoria’s. This was too much change far too soon, and Connell demonstrated remorse by buying up as many of the stamps as could be found and burning them on his front lawn.

Connell wasn’t the only one receiving mixed signals from Britain. The Colonial Office was increasingly demanding loyalty while services and benefits were being systematically withdrawn. Free trade and greater political autonomy obliged the colonial leadership in British North America to think more strategically about their future, including alternative political structures. But it would be a mistake to think that Confederation was the only outcome being considered, or that it was an inevitability. It was neither.

Several options presented themselves, the foremost being joining the United States. Together or separately, by the 1860s all of the colonies at some point considered annexation. Barely a decade had passed since the campaign for annexation had been at the height of popular discourse and held its widest appeal. Since then, the idea had lost much of its support, but there were still many enthusiasts for the idea. As we shall see, it was an option considered very seriously in the Red River Colony as the prospect of union with the Americans held the allure of better access to large and expanding markets. Even in Canada it was easy to see that union with, say, Prince Edward Island would never have the same economic impact as closer trade ties with the United States.

Another option was the status quo, which was the choice Newfoundland made for another 80 years. Carrying on without change in the Province of Canada would mean thrashing through some pernicious constitutional and operational difficulties, but couldn’t be ruled out. Those who supported this option looked to other jurisdictions — Italy comes to mind — that had survived and even thrived under governments made of fragile coalitions. Many of Confederation’s critics, Nova Scotia’s Joseph Howe for one, argued for this: “Now my proposition is very simple,” he said, “It is to let well enough alone.”[footnote]Quoted in Ged Martin, “The Case Against Canadian Confederation 1864-1867,” in The Causes of Canadian Confederation (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 1990), 27.[/footnote]

Smaller unions were also considered. Maritime union was, briefly, a very real prospect, one that would have created a single colony out of three (four if Newfoundland joined in). Union was thrust on the two West Coast colonies in 1866: Vancouver Island became just another region in the colony of British Columbia, although it did win the capital away from the mainland. And in Canada proper, George Brown made it clear that the minimal change he would accept in exchange for his cooperation was a federal reorganization of Canada West and East. This would have necessitated the dissolution of the Act of Union only to create a voluntary union of equal partners with separate legislatures and a central administration. From eight separate colonies in 1865, four could have coalesced by 1867.

One must ask, too, if any of these solutions really addressed the question at hand. If the issue was replacing British trade and/or American reciprocity, then the colonies could have pursued a customs union (sometimes called by the German term, zollverein). If it was the business of getting a loan to build a railway, then better finances, not a constitutional change, would do the job. If the issue was the defence of British North America against the Americans, who housed a huge post-Civil War army, then the only conceivable answer was closer ties with Britain, not semi-independence.

In short, under these alternative scenarios, the 1870s could have opened with a federal Canada stretching from Lake Huron to the Gaspé, a reunited Acadia on the East Coast, and Red River (or perhaps Assiniboia) added on to the U.S. Midwest. British Columbia could well have vanished into what, in the 20th century, was promoted as Cascadia, a region stretching from California to Alaska. Or the colonies might have clung more tightly to the hem of Mother Britain’s skirt in an imperial federation and eschewed any kind of union at all.

Every one of these options was serious considered in the 1860s. The solution at which political leaders arrived was influenced mainly by external factors and specific ambitions. This chapter surveys those elements and the implications of the new constitutional configuration. It also explores the emerging relationship between Canada and the West, without which the proposal for a union of colonies might not have proceeded. (Turning it on its head, if there had been no colonial union, there would likely have been no Canadian annexation of the West either.) Finally, this chapter pays some attention to the changes underway in the economy among Aboriginal peoples and culturally in British North America as the 1860s drew to a close. It is important to realize that while this decade is usually dominated in Canadian history by the achievement of a new constitutional arrangement, it was also a springboard for vast, sweeping changes in social and economic life. By the 1880s, Canada as a whole was experiencing a full-blown industrial revolution while Aboriginal peoples on the Plains faced famine and landlessness. These and other critical moments in Canada’s history have their roots in the 1860s.

Figure 14.2 William Raphael’s Behind Bonsecours Market, Montreal (ca. 1866) shows women and children in a public space, ships under sail and steam, farm products, and a sense of both busy-ness and leisure.

Figure 14.1

Charles Connel by Сдобников А. is in the public domain.

Figure 14.2

Behind Bonsecours Market by File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske) is in the public domain.

Historical approaches to British Columbia follow imperial avenues. From a Canadian perspective, we approach it along the routes of the North West Company (NWC), through the northern Rockies and along valleys and passes to Bella Coola or the Columbia River. From a British or Spanish perspective, we come at it from the sea and from warmer waters to the south, perhaps via Hawaii. Had Russia successfully annexed everything on the West Coast, the historical approach would reflect that northern intrusion — a story of Siberian traders from Kamchatkan ports, incrementally working their way from Alaska to California. An American imperial approach focuses on the mainland, specifically on the Oregon Trail, though it should make room as well for the multitude of entrepreneurial Bostonian captains sailing around Cape Horn on long-haul trade expeditions. The American view would also observe the enormity of Washington, D.C.’s claim on the territory and the impact of Americans throughout the gold rush years.

Once it was determined to the satisfaction of Europeans and Euro-North Americans that there was no water passage through the territory, they started to think of it in terms of ports, coves, forts, and corridors. What is missing from these competing imperialist views is an appreciation of the region as a human space, a dense patchwork of cultural territories for which “getting in” and “getting out” are irrelevant concepts.

Historian Jean Barman coined the phrase “the West beyond the West” to describe the territories that would eventually coalesce into British Columbia by 1871. Other terms that have been used include Trans-Mountain West, the Cordillera, New Caledonia, New Albion, the Pacific Northwest, and Cascadia (this last one lumps together British Columbia with the American states of Washington and Oregon). None of these labels are perfect, not least because British Columbia covers such a vast territory, one that includes the prairie lands of the Peace River District in the northeast, the rolling and almost pastoral Cariboo plateau, and the desert and semi-desert terrain of the Okanagan and Thompson Valleys, as well as the mountainous landscape throughout and the fjords and islands of the coastlands. Much of the region is as unlike the “Pacific Northwest” as can be imagined. More to the point, British Columbia is, with the exception of the Peace District, utterly separate from the Prairies. For that reason, Barman’s “West beyond the West” works nicely to remind us that there is a whole world of regions within a region that lies outside the more easily conceptualized prairie landscape we refer to simply as “the West.”

The period from 1740 to 1874 in the farthest west was a time of Aboriginal cultures adapting and adopting European and Asian technologies and matériel successfully. It also encapsulates a catastrophic loss in populations brought on by epidemics of exotic diseases. While European and American merchants struggled to find the sweet spot in a fur trade with potentially enormous profits but very high costs, Aboriginal communities found themselves confronting internal competition and conflict as well as gunboat diplomacy. European impact on the region was, nevertheless, limited until the 1858 gold rush, at which point the local contact period accelerated very suddenly and in ways unseen elsewhere in British North America. Combined with the arrival of an industrial revolution, these changes drove significant political changes at a record pace. There was no “pioneer stage” in the West, just a race to industrial scales of production that began in the Victorian era and overshadowed nearly a century of regional commerce. Toward the end of this period, a single colonial regime had emerged along with many familiar themes associated with power and elitism. Throughout it all, Aboriginal people took a stand against the newcomer populations and cultures (in the 1860s in particular), and many of the issues they addressed then remain unresolved in the 21st century.

Figure 13.1

Plano del Archipielago de Clayocuat 1791 by Pfly is in the public domain.

Histories of childhood present special challenges. First, assuming that one is fortunate enough to pass through childhood and not succumb to the many dangerous diseases, it is a transitional phase in life. However much it might define one, it will only do so for a certain period of time and then it is left behind. One may be a female or an Aboriginal person or a farmer for the entirety of one’s life, but no one is a child for more than the first few years.

The second challenge is how to define childhood. Clearly there’s the period of utter dependency that most societies would agree constitute infancy and that usually lasts four to six years. After that, what distinctions does a society and culture make between a seven-year-old, for example, and a 14-year-old? What criteria are used to define the qualities of childhood and its end? Across the many cultures of British North America and Aboriginal Canada and across many centuries, the definition of childhood has been both diverse and fluid.

Third, the history of childhood is limited by the lack of personal records. Most children in the past were insufficiently literate and rarely self-reflective enough to provide first-hand accounts of their lives. This changed somewhat in the 19th century when institutionalized education emerges as a shared aspect of child development, one that taught children how to give voice to their experiences. Nevertheless, the record in past centuries is patchy at best. And our own values and prejudices about childhood come to bear. As historian Robert McIntosh recently wrote,

The history of childhood has been reconstructed through studies of adults and their activities – and children’s responses to these. Only rarely is the agency of children recognized in the historical literature: children tend to be portrayed as passive beings who are the objects of welfare and educational strategies. The history of childhood becomes the history of the efforts of others on children’s behalf. [footnote]Robert McIntosh, “Constructing the Child: New Approaches to the History of Childhood in Canada,” Acadiensis XXVIII, no.2 (Spring 1999).[/footnote]

What becomes clear in a study of childhood over even a relatively brief stretch of historical time is how the experience is historically contextualized. Childhood, probably more than adulthood, reveals the extent to which we are shaped less by biology and family and more by historical forces. Nature and nurture are important but it is history’s hand that rocks the cradle.

Figure 12.1

Clayoquot girl by BotMultichillT is in the public domain.

Admiral Horatio Nelson, the victor of the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, was memorialized shortly after his death by pedestal columns erected around the empire. The Nelson Monument in Montreal was the first in British North America and elicited different reactions from the Anglo-Protestants and the French Catholics. Completed in 1809, the column provides Nelson with a good view over the city, is visible for miles, and functions as a daily reminder of the triumph of British naval (and commercial) power both across the Atlantic and in North America. At 69 feet tall, it is not the tallest of the Napoleonic Columns (the one in Trafalgar Square in London stands 170 feet high), and Brock’s Monument is taller still.

The first memorial to General Isaac Brock was erected on the Niagara River at Queenston Heights in the 1820s, when the War of 1812 was still very much a recent memory. It originally stood 135 feet tall and was easily visible from the American side of the Niagara gorge. The column — with a viewing platform at the top — became a pilgrimage site for Upper Canadians. For Tories it had a special meaning as the place where, at the cost of Brock’s life, the American invaders were repelled. In the budding myth of English Canadian nationhood it would mark the spot where the new nation bloodied its neighbour’s nose. The fact that the Canadian militia was a tiny and reluctant fraction of the troops involved was neither here nor there; growing the legend of loyalism and duty was the point of the exercise. This narrative was perpetuated in song in 1867 by Alexander Muir (1830-1906) in “The Maple Leaf Forever,” often regarded as Canada’s first national anthem. In the second verse, Muir wrote:

At Queenston Heights and Lundy’s Lane,

Our brave fathers, side by side,

For freedom, homes and loved ones dear,

Firmly stood and nobly died;

And those dear rights which they maintained,

We swear to yield them never!

Our watchword evermore shall be

“The Maple Leaf forever!”

Muir was a Scottish immigrant whose father could not possibly have stood firmly or any other way alongside Brock. Setting that literary exaggeration aside, what Muir wished to convey is that Canadians in 1812 had fought for freedom from American republicanism while protecting their families from a savage Yankee attack.

In part, Muir was reflecting his own experiences. At 45 or 46 years of age, he was a member of the Queen’s Own Rifles, a Toronto regiment that served in 1866 at the Battle of Ridgeway, the year before both Confederation and his writing of “The Maple Leaf Forever.” Ridgeway is barely a day’s march south of Queenston Heights, on the same Niagara frontier that Brock defended successfully 50 years earlier. For Muir, a loyal Orangeman and a proud Scot, fighting the Fenian Invasion of 1866 was a matter of saving Canada from the barbarian Irish and Irish-Americans, and as far as he was concerned Brock had done nothing less in 1812.

Not everyone felt the same way. To some, Brock was representative of the haughty and corrupt Family Compact, the Tory cabal that wrapped itself in the flag of loyalism and exploited an extensive system of patronage for its own gain. Repeated efforts were made to achieve political reform through peaceful means, but they failed on every occasion. Opponents of the regime were expelled from the colony; some were imprisoned. In the 1830s republican sentiment in the colony was growing and exploded in a brief and doomed rebellion. The rebels who weren’t captured, imprisoned, or hanged were driven across the border into the United States. In 1837 some made their way to Navy Island in the Niagara River, in Canadian waters. They declared a provisional Canadian Republic and plotted, unsuccessfully, an invasion. One of the armed exiles was an Irish-Canadian named Benjamin Lett (1813-1858). As the rebel movement lost steam in 1840, someone — many believed it was Lett — set off an explosion that tore the top off of Brock’s Monument.

The decapitated and ruined tower was transformed in an instant into a very different memorial. Its shattered profile became a powerful testament to the tensions that existed in Upper Canadian society between those whose history was bound up in anti-revolutionary Loyalism, oligarchical authority, and the power of the local garrisons on the one hand, and those colonists who saw themselves as North Americans first, heirs to a tradition of relative colonial autonomy, advocates for democracy, and even foes of the monarchy.

A new monument to Brock was completed in 1860. At 184 feet, it is comfortably taller than Nelson’s Column in Trafalgar Square, making it the tallest of all the Napoleonic Wars towers. It would have been six years old during the Battle of Ridgeway, and there’s some possibility that Alexander Muir passed within view of it as his regiment marched south to face the Fenians. Perhaps he saw it again as his unit retreated in haste after the first volleys near Fort Erie. The Queen’s Own Rifles were mocked by their peers as the “Quickest Out of Ridgeway,” but they faced a force of Irish-American nationalists hardened by three years of Civil War service. The battle cost the lives of 32 Canadians and was an embarrassment for the authorities in Canada West, even though the Fenians abandoned the attack. In other words, it was no Queenston Heights and there were no retroactive attempts to mythologize it.

Among the embarrassed parties after Ridgeway was the Minister of the Militia, none other than John A. Macdonald (1815-1891). Macdonald was then a young and inexperienced militiaman (not unlike the composer Muir). He was visiting Toronto from Kingston and was called up to disperse the rebels led by the radical reformer William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861). It is possible that the future prime minister even exchanged fire with Benjamin Lett, who may have been present among the rebels during the Battle of Montgomery’s Tavern.[footnote] The fact that Macdonald was exchanging fire with the grandfather of future prime minister William Lyon Mackenzie King is worth considering as well.[/footnote]

In the 20th century Canada acquired the epithet, “the peaceable kingdom.” As we’ve seen, the period up to 1820 was marked by anything but peace. The historical record bulges with accounts of inter-empire warfare, ongoing battles between the Aboriginal occupants of North America and newcomers everywhere from Newfoundland to the West Coast, and struggles between settler societies. There were also violent conflicts between British North Americans, such as the fur trade wars and anti-Irish riots. If we think of the Niagara River as the sharp edge of Canadian-American relations, there were three occasions when blood was shed there in the half-century between 1812 and Confederation — once for each of three generations. What happened along the Niagara frontier consistently involved questions about Britain’s relationship with its colonies and where power resided in the colony itself. And, of course, each struggle pointed to the challenges inherent in British North America’s relationship with the United States, one of many important issues that drove political debate in the 19th century.

This chapter places the critique of the established oligarchy in the context of larger political changes taking place across the Atlantic world. The protests that led to rebellion, bloodshed, the Durham Report, the Act of Union, and a nascent Canadian political culture are examined, as are the changes and continuities to be found in the Atlantic colonies.

Figure 11.1

Monument Nelson Montreal by Jeangagnon is in the public domain.

Figure 11.2

Brocks Monument by YUL89YYZ is in the public domain.

Figure 11.3

1st Brock’s Monument damaged by pload Bot (Magnus Manske) is in the public domain.

The Napoleonic Wars ended French hegemony in Europe and provided Britain with newfound elbow room in an evolving world economy. British North America, too, could afford to relax a little: American expansionists along the eastern seaboard turned their hungry eyes from the North to the West. The wars of the early 19th century were fought on battlefields and at sea, but they were also in the new workplaces that would come to be known as “industrial manufactories.” The half century that followed 1818 would see the spread of new ideas and practices, some of them associated with empire, others with the scientific and technological enlightenment that would lead into economic and industrial revolution.

While there were many significant changes in the economies of British North America, continuity still existed. Agriculture was a leading force in the economy, as was the fishery. These were joined by other staple production activities that gave shape to the colonies and their societies just as the fur trade informed much of life in New France.

What most distinctly marks the period from 1818 to 1860 is British North America’s changing relationship with the world marketplace. The loss of preferential tariffs in Britain changed the economic stakes, but it also changed the psychology of trade. If the empire wasn’t the raison d’être for the colonial economies, what was? Even if industrialization and social change took place slowly in British North America, that wasn’t the case in Britain. There, British North Americans could see from a distance a future comprising densely populated cities whose purpose was not commerce but production of goods. They could see, too, changes in infrastructure and sources of energy: wood and wind would give way to coal and steam by Confederation. The colonial economies of 1818 would either evolve significantly by 1860 or they would be on the precipice of enormous change. Either way, in both the United Kingdom and the United States, British North Americans had examples to which they could turn. These models were both physical and intellectual: this was an era of changing economies and changing minds.